Guest Album Review – “Take Care” by Drake

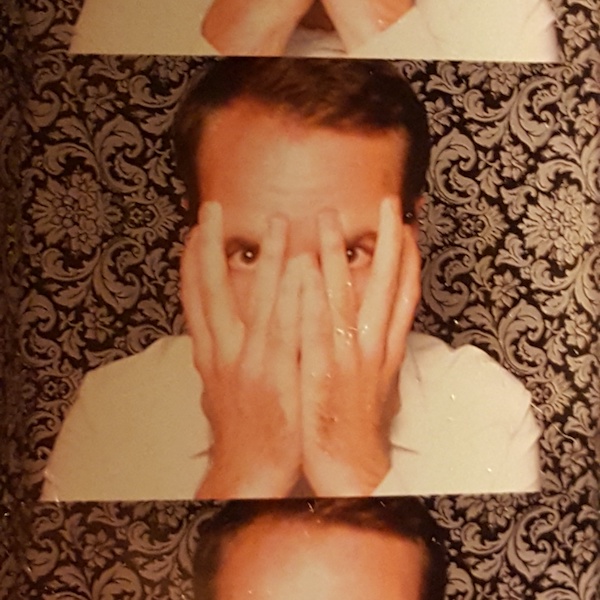

This guest review was originally part of a music blog project I created called Under The Deer. Since that site won’t be around forever, I’m archiving these wonderful reviews and their accompanying illustrations here. Writer and illustrator listed at end of the review.

In his influential 2010 book Retromania, critic Simon Reynolds argues that the easy accessibility of recent pop music has had a stifling effect on creativity. Once upon a time, record labels regularly “deleted” old LPs, and few albums were reissued after their immediate release cycle. If you didn’t buy a record when it came out, it would take you no small effort if you wanted to hear it again ten years down the line, like a connoisseur of trashy video games trucking down to a landfill in Alamogordo with a spade. This had the effect of diluting influence: if you wanted your drums to sound like Can circa Tago Mago, you couldn’t just go to any old shop to buy the LP, let alone download it, let alone sample it. More often than not, you were forced to reproduce the sound in the studio as best you could recall it—and memory itself is inexact. The sound you ended up with might bear only the faintest resemblance to what you were going for, but through that flawed reproduction process, you might have stumbled onto something new.

In Reynolds’ conception, even the best music of the 2000s is pastiche and collage. Bearded indie rockers lovingly assemble records destined to be described as “Band X meets Band Y, with a hint of Band Z” by record store sommeliers, while EDM bangers recycle old material for a hit of nostalgia (sometimes cynically). I don’t entirely disagree with Reynolds’ conclusions, but it’s worth noting that the wheel has already turned from the era he was writing about. Mash-ups, the most literal example of “retromania,” have returned to the hinterlands of YouTube, while young artists seem less inclined to talk about their tapestry of influences than their social justice bona fides. The change is generational and has less to do I think with a difference in approach as it does with attitude. Being older, and a music historian to boot, when Reynolds’ hears a sample he can’t help but recall its original context; to him, most samples are by default referential. But for many new artists (and listeners), the past is simply raw material to be reduced in the service of a new vision. Reynolds could hardly have anticipated a rapper would emerge almost in tandem with his book who would embody this omnivorous and (productively) self-absorbed new status quo.

Drake’s first LP, Thank Me Later, dropped just a few months before Retromania was published, and its follow-up Take Care probably hit stores around the same time as the paperback edition. Somewhere in that 16-month window, the Canadian rapper-singer emerged fully-formed as the franchise that would go on to launch a thousand think pieces and stack up video game-level numbers on the Billboard charts. Post-808s Kanye in both production and content, Take Care establishes the basic OVO Sound, which would become as ubiquitous as Prince’s Minneapolis Sound in the ’80s: worlds of echo, muffled percussion, minimalist synths, like rain beating against the glass walls of a Toronto condo. But it’s the title track, a slight outlier on the record, that says the most about where we’re at in music today.

Decades before “Take Care” was soundtracking many a drunken, post-club reconciliation, there was “I’ll Take Care of You,” a song written by Brook Benton and first recorded by the great Bobby “Blue” Bland in 1959. Bland’s version is a smoky, hypnotic soul blues that glides along on little more than a pattering snare and a vamping Hammond organ. It was never a huge hit for Bland (#89 on the charts), but it would become a bit of a standard over the years. Crucially to our story, gravel-voiced jazz poet Gil Scott-Heron was enough of a fan to record it for his well-received 2010 comeback record I’m New Here. Now, this is where it starts to get more complicated. Scott-Heron shared a label with the xx, an English indie band whose producer Jamie “xx” Smith was subsequently hired to remix the whole record. Now titled “I’ll Take Care of U,” Jamie xx reimagined the track as a clubby yet melancholy fusion of Balearic house, dubstep, and the xx’s introspective guitar pop. Scott-Heron’s voice is scattered all over the track through echoes and spliced samples, while an icy, reverberant guitar lick serves as the song’s most instantly recognizable motif. Only then did Drake and his personal producer Noah “40” Shebib get their hands on it, adding Rihanna and cropping the title (and making just about everyone else in the tree above a bit richer).

That makes “Take Care” a (hold your breath) hip-hop interpolation of a post-dubstep remix of a postmodern blues cover of a fifty-year-old soul song. Despite this polyglot ancestry, it doesn’t play the kind of meta games with its form that Reynolds takes issue with. It feels self-contained, using these existing elements to tell its own story. In truth, 40 doesn’t make many changes to “I’ll Take Care of U” beyond simplifying the bass and drums to create a rhythmic platform for Drake’s rhymes. The more significant changes are matters of arrangement: Jamie xx’s track is house music, while Shebib’s revisions return it to a traditional pop song structure. And it’s within those familiar environs that Drake and Rihanna take over.

It helps that the two singers have such a public history, having been on-again, off-again lovers for years. While Rihanna’s biggest hits as of 2011 (“Umbrella,” “Only Girl (in the World),” “We Found Love,” the appalling “Love the Way You Lie”) seemed to reveal little about her, Drake’s palace was built on TMI. Perhaps the genuine intimacy we sense in their voices stems from their real-life closeness; or perhaps simply knowing that they are close influences our perception of the duet. However, it gets there, “Take Care” feels like an honest conversation between real people, even though the words Rihanna sings were written fifty years before Drake’s. The track wraps so snugly around their star personas it feels like it was written for them from the ground up. Drake’s performance is among his best, imbuing some of his most universal lyrics with empathy, protectiveness, and compassion.

“Take Care” occupied a unique middle ground in 2011-12’s Top 40, between the dominant pop house formula and Adele’s piano-driven torch songs, but with each passing year that middle ground has expanded. Drake himself has taken the formula to even greater chart success with tracks like “Hold On, We’re Going Home” and “One Dance,” but he’s also been joined on the pop charts by progressively weirder Lil Wayne/Drake progeny like Future, Migos and Young Thug, and genre-melting auteur statements from established artists like Beyoncé and Solange. Take Care, the album, looks more like a milestone of 2010s rap with each passing year. On the one hand, you have hints of an era just closed, like the forgotten Just Blaze banger “Lord Knows,” which sounded like a slight throwback even at the time, and the field recording of Scrooge McDuck counting his money in the studio that closes “We’ll Be Fine.” On the other, there are invaluable snapshots of future peers (Nicki Minaj, The Weeknd) and rivals (Kendrick Lamar) just prior to their own ascensions to superstar status. It even helped popularize fun ’10s tropes, like having André 3000 materialize on a deep cut and casually drop the tightest verse on the album, or relegating the hottest single to “bonus track” status (“The Motto”).

At well over 80 minutes of night-of partying, morning-after disappointment, it’s a bit of a slog even for fans, but it seems like a whole generation of listeners has come away from Take Care feeling as though their experiences at the turn of a millennium are validated by this music. Everyone’s drunk-dialed an ex who has moved on, or wanted to. Everyone has tasted some of the good life and found it more hollow than they might have imagined. Though the album snatches samples and interpolates a bevy of sources, it’s as personal a statement as any in pop music. And because we can believe this is “the real Drake,” millions have made it the soundtrack to a vital period in their own “real lives.” More than the catchphrases and memes, that will remain Drake and his collaborators’ most lasting contribution.

Contributors

JM Francheteau is a writer based in Toronto, Canada. His writing has appeared in Arc Poetry Magazine, The Puritan, Broken Pencil, Bad Nudes and elsewhere.

Mia Batajić is a visual artist, illustrator, designer, human in progress from Belgrade, Serbia. Lover of expressive art, crooked lines and color.