Tag: imported From Under The Deer

March 28, 2018

-

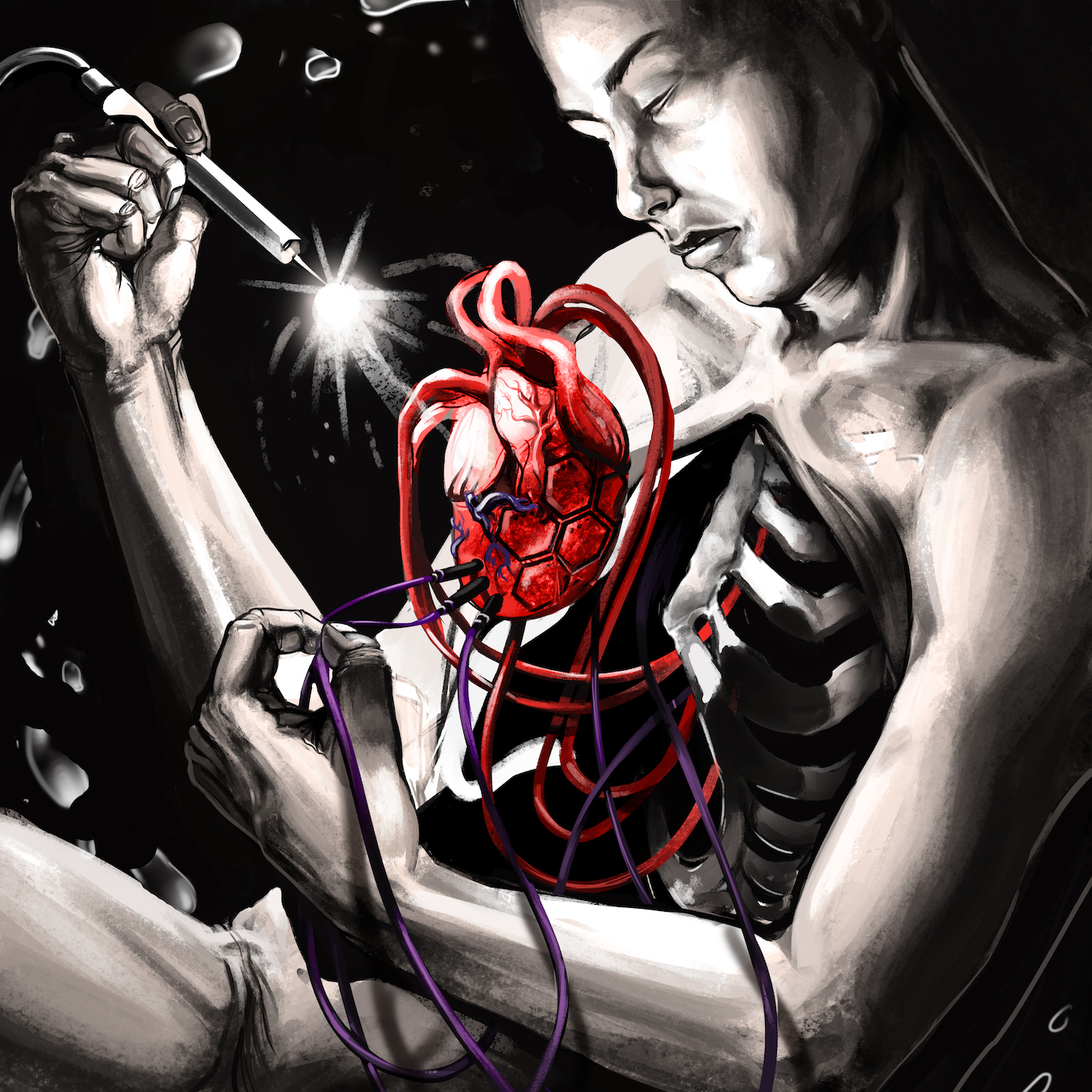

Guest Album Review – “Kid A” by Radiohead

This guest review was originally part of a music blog project I created called Under The Deer. Since that site won’t be around forever, I’m archiving these wonderful reviews and their accompanying illustrations here. Writer and illustrator listed at end of the review.

Radiohead might be the best band since The Beatles. For sheer range of effect, lyrical subtly, sonic virtuosity, and philosophical weight, they have come to define (and redefine) the last twenty-three years in popular music—first with The Bends, a spacey pop-rock masterpiece that featured such classics as “Fake Plastic Trees,” “Just,” “My Iron Lung,” and “Street Spirit,” and then with their most popular—and, some would say, greatest—album, OK Computer, which cemented their reputation as innovative rock gods. “Karma Police” and “No Surprises” are beloved by fans and non-fans alike, and “Paranoid Android,” which was voted the Best Song of the Last 15 Years by NME, has become a concert staple, along with “Exit Music,” “Let Down,” and the ironically titled “Lucky.”

Since 2001, Radiohead has released five albums, among them Amnesiac, their most challenging, jazzy, and (arguably) disjointed album, featuring everyone’s favorite downer, “Pyramid Song,” the hypnotic “I Might Be Wrong,” and the album’s closing dirge, “Life in a Glass House.” Hail to the Thief, the band’s protest album, which was seen by many as a return to form—at least their 90s rock form—gave us their first radio-friendly single in years (“There, There”) as well as “2 + 2 = 5,” a ferocious head-banger, and undervalued gems like “Backdrifts” and “Wolf at the Door.”

In 2007, Radiohead released their most crowd-pleasing album to date: In Rainbows, a nearly flawless 43 minutes of foot-stompers (“Jigsaw Falling into Place,” “15 Step,” “Bodysnatchers”) and tender ballads (“House of Cards,” “Nude,” “All I Need”), not to mention the band’s best song (“Reckoner”) as well as their saddest (“Videotape”). Their much-anticipated follow-up, The King of Limbs, however, was more problematic. The first half contained badly mixed, oddly static tracks like “Bloom” and “Feral,” while the second half featured the warm and groovy “Lotus Flower,” the gorgeously sad “Codex” and “Give up the Ghost,” and the genuinely uplifting “Separator.”

2016’s A Moon Shaped Pool was a welcomed change of pace, combining the emotional intimacy of In Rainbows with a new string-heavy aesthetic—both acoustic and orchestral. Songs like “Burn the Witch,” “Identikit,” and “Ful Stop” reminded listeners that Radiohead still knew how to rock (albeit in new directions), and the delicate, swooning violins of “The Numbers” provided a classical counterpoint for the album’s piano-driven highlights: “Daydreaming,” a lush, sparkling search for lost time, and “True Love Waits,” the dark, melancholy twin of a live track recorded nearly fifteen years before.

Needless to say, any number of albums could be considered Radiohead’s “best”.

Most choose OK Computer, for obvious reasons, while many younger fans prefer In Rainbows’ warm accessibility to the harsh, cerebral satire of the 1997 game-changer. Meanwhile, jazz nerds love Amnesiac, classical buffs celebrate Radiohead’s latest effort, and political activists—railing against everything from pollution to corruption—tend to favor Hail to the Thief. Some even prefer the sometimes-soft-sometimes-hard-rock vibe of The Bends. No one, however—including Radiohead themselves—likes their debut, Pablo Honey, enough to rank it first (or even second or third—or, for that matter, fourth or fifth), and, despite its moments of brilliance, few would rank The King of Limbs much higher.

There is one album, however, which has so far gone unmentioned: Kid A. Rolling Stone ranked it the best album of the 2000s, as did Pitchfork, who gave it not one, but two elusive 10/10s—the first upon its initial release, the second after its recent reissue. The idea, in 1999, that Radiohead could not just match but transcend OK Computer seemed unlikely, akin to asking Pink Floyd to top Dark Side of the Moon, yet one year later that’s exactly what happened—and not by making OK Computer: Part Two. Instead, Yorke and his not-so-merry band of brothers traded their guitars for keyboards, tossed their non-rock-related influences—such as jazz, electronic, and classical—in a blender, and poured out a bizarre, unnerving puree of sonic experimentalism.

The opening track, “Everything in Its Right Place,” launches the listener into an otherworldly—yet strangely familiar—soundscape. “Everythiiiiinnnnng, everythiiiinnnggg,” Yorke croons, his gentle, nasal falsetto floating from syllable to syllable, caressing you into a kind of demonic trance. Right away, you sense a hint of irony in the title: everything is either not in its right place or in its right place, but in a bad way—a theory reinforced by the subsequent lines: “Yesterday, I woke up sucking a lemon…There are two colors in my head…What was that you tried to say, tried to sayyy, tried to sayyyyyyyy?” (A good question, which the song seems to ask itself.) Clearly, we’re not in Kansas anymore—or are we? Many of us, no doubt, feel upon awakening like we’re “sucking a lemon,” both literally and metaphorically: morning breath, morning ennui. Life leaves a sour taste in the mouth, especially when you’re tired and reluctant to meet it. The “two colors” in Yorke’s head seem to suggest anxiety—conflicting thoughts, self-defeating desires—or a kind of depression-inspired monotony: life in black and white, the world deprived of meaningful gradations. The final line, which both bludgeons you into submission and catapults you toward the sublime, connotes an inability to communicate and thus connect with other minds. Isolation, alienation, frustration—this song (and Kid A) in a nutshell.

The title track continues in a similar vein, this time with Robot Yorke taking over the vocals, followed by “The National Anthem,” which externalizes the themes of its predecessors, shifting the focus to “everyone around here,” who is “so near,” who has “got fear,” and who is “holding on.” The thudding baseline and crashing cymbals suggest a more traditional rock song but don’t be fooled: two and a half minutes in, the track becomes an extended jazz freak-out, inspired by the more chaotic side of Charlie Mingus. The next tune, “How to Disappear Completely (And Never Be Found),” pulls a sonic U-turn, trading everything electric for their acoustic counterparts—not to mention slowing the tempo, softening the tone, and filling out the folk-infused texture with wailing organs and heavenly vocals. The lyrics are as plain and authentically painful as the title suggests (“That there, that’s not me…I’m not here…This isn’t happening”), and during the cathartic crescendo the sadness—as well as the volume—gets turned up to eleven.

“Treefingers,” on the other hand, barely moves. More tone poem than song, it provides an ambient respite from the emotional swings and existential roundabouts of everything that came before. Tonally, it returns to the icy, tranquil terrain of “Kid A,” lulling you to sleep before shaking you awake with “Optimistic,” the most (ironically?) upbeat track on the album. Although the lyrics are mostly sardonic, the refrain has the trappings of sincerity: “You can try the best you can…The best you can is good enough,” which is then undercut by “I’d really like to help you, man”—the prelude to a flimsy excuse. Vague enough to imply everything, Yorke could be singing about the state of the world or the state of your soul, and, in this case, the ambiguity is reassuring. One senses light breaking through the Kid A clouds.

That is, until “In Limbo” starts, and you’re thrust back into hell. No song so aptly embodies the sensation of mental instability. The awkward, atonal structure, the cacophonous chords and mismatched layers of instrumentation—everything underscores the sensation of “living in a fantasy life,” if by “fantasy” Yorke means delusions and nightmares. Internal Hell then gives way to External Hell, as we abandon Yorke’s psychological limbo for the bleak and bare terrain of “Idioteque.” One of Radiohead’s few dance-inducing tracks, this visionary gem is equal parts catchy and jarring, hypnotic and disturbing. The lyrics, comprised of apocalyptic sound-bites (“Ice age coming…Who’s in the bunker?…Women and children first”), overshadow a soul-crushing beat and spine-tingling tones, sampled from the early days of electronic music. The ethos of the age is also evoked in phrases like “take the money and run,” “I haven’t seen enough,” and “I laugh until my head comes off.” The most haunting line, however, is the most apparently harmless: “Here, I’m allowed everything all of the time.” Our permissive culture—ecologically, economically—has created a world of self-obsessed, hedonistic anti-citizens (an “Idioteque,” if you will) hell-bent on bending things until they break. A century-defining song, “Idioteque” encapsulates our current predicament—as well as its inevitable outcome—more effectively (and more succinctly) than any dystopian novel or political text.

The penultimate track, which starts where “Idioteque” left off, is appropriately titled “Morning Bell.” The opening lyrics, “Morninnnn belllll, morninnnn bellllll,” sound like a nasal alarm clock designed to pull you out of a nightmare and thrust you into a waking one. Yorke’s repeated request to be “released” adds another layer of irony: released into the world or simply another dream—or an idealized combination of the two? The answer is unclear, but the album’s final song, “Motion Picture Soundtrack,” provides some ominous clues. From talk of “sleeping pills” and “cheap sex” to a longing for someone’s arms, it’s clear that this harp-filled lullaby isn’t meant to comfort. “I think you’re crazy, maybe” sums up the album as a whole: Kid A is surely the product of a troubled, perceptive mind with bleak ideas about the world and where it’s heading, but if Yorke and Co. sound “crazy,” it says more about the listener than the band—hence the qualifier “maybe.” At the end, Yorke sings, “I will see you in the next liiiiiiiiife,” and floats into the ether. Whether this signals a kind of death or the desired release of “Morning Bell,” it comes as a relief for the listener, who feels for the first time in 48 minutes that everything is finally in its right place.

Which begs the question: why listen to (let alone like) this dark and difficult album? Why is it considered by so many critics and fans to be the height of Radiohead’s achievement? Surely OK Computer is more accessible, In Rainbows more rewarding. Surely an album with three songs of questionable quality—“Kid A,” “Treefingers,” and “In Limbo”—can’t be considered a flawless opus. (“Treefingers” overstays its welcome, “Kid A” weirds itself out, and “In Limbo” does both.) Each is an integral part of the Kid A experience, but few Radio-Heads seek them out beyond the context of the album.

That said, Kid A flows seamlessly from song to song, idea to idea, emotion to emotion. It is unified and coherent, expansive and internal, visionary and down-to-earth. One could mention its pervasive influence, its blend of psychological insight and musical sophistication, or simply its jaw-dropping prescience, but the reason this album remains so revered is simple: it’s great in the way that Sgt. Pepper or Revolver is great. It lets you know you’re not alone; it shines some light (however dim) in the darkness. For ten tracks, Thom Yorke becomes a poet, a prophet, a political activist, a ghost, a robot, and a manic-depressive—in short, he becomes a person, a disenchanted, discombobulated citizen of the 21st century.

Contributors

Chris Gilmore is the author of Nobodies. His writing has appeared in McSweeney’s, Hobart, The New Quarterly, Matrix, and The Puritan. In 2017, he won the U of T Magazine Short Story Contest.

Rekka Bellum is an illustrator who lives, travels and works aboard a sailboat. Common illustration themes include fungi, root vegetables, skeletons and sad animal people.

March 27, 2018

-

Guest Album Review – “Floating Into The Night” by Julee Cruise

This guest review was originally part of a music blog project I created called Under The Deer. Since that site won’t be around forever, I’m archiving these wonderful reviews and their accompanying illustrations here. Writer and illustrator listed at end of the review.

“What do you see David? Just talk to me.”

“OK, Angelo. We’re in the dark woods now, there’s a soft wind blowing through some sycamore trees, the moon’s out, you can hear the hoot of an owl. Get me into that beautiful darkness with the soft wind. From behind the trees, in the back of the woods, there’s this lonely girl. Her name is Laura Palmer.

She’s very sad… That’s it! I can see her! She’s walking towards the camera!

She’s getting closer… Now she’s starting to leave… Fall back. Keep falling. Keep falling. Keep falling. Just go back into the woods…”

It’s a short video. We see Angelo Badalamenti behind his keyboard. He’s setting the scene. He plays an embryonic chord progression, narrating the events of an evening he spent with David Lynch. It’s a simple dialogue: Lynch describes the Twin Peaks of his mind as Badalamenti responds with melody. Lynch has a vision: a collage of imagery will slowly begin to converge into a coherent form, first as spoken word, and then, ever so subtly, under Badalamenti’s fingers. The result is frankly faint-making. The heart-wrenching song we heard was soon to become Laura Palmer’s theme in the now-legendary TV show Twin Peaks, with Julee Cruise lending her velvety vocals to its studio version, aptly titled “Falling”.

David Lynch imagined a dark forest, Angelo Badalamenti made a lonely girl manifest in its darkness, and Julee Cruise came to be the soft wind, rustling the Sycamore leaves into a reverberant nocturnal hush. With lyrics by Lynch, music by Badalamenti, and vocals by Cruise, the trio wrote an alleged 40 songs, only ten of which appeared in the final track listing of Floating Into the Night.

Julee Cruise’s Floating Into the Night has haunted me for years. It’s an incredibly misleading album. At first, its warm tones, intermittent mellifluous brass and omnipresent wall of synthesizers might sound comforting; But it doesn’t take long to find deeply unsettling truths at its core, an uncanny sense of discomfort that can’t be shaken easily.

But First, let’s take a few steps back to look at the bigger picture. During the production of David Lynch’s Blue Velvet (1986), when the rights to This Mortal Coil’s rendition of “Song to the Siren” proved too expensive, Angelo Badalamenti was tasked with recreating the same dreamy quality in an original composition of his own. Having previously worked with Julee Cruise, she was to become the vocalist for “Mysteries of Love”, a song that appears in Floating Into the Night a few years later.

Though Lynch had received critical acclaim previously, it was Blue Velvet that truly brought his obsession with small-town America to a wider audience. Lynch was to become a household name in American arthouse cinema; injecting new vigor into the independent film scene. David Lynch has been discussed ad nauseam, but to further understand the underlying structure of Floating Into the Night, certain aspects of his work need to be discussed.

Born in 1946, the post-war economic growth was to be the eerily optimistic era in which Lynch spent his childhood. We’ve all seen the posters, we’re familiar with that smile: the docile smile of a white middle-class housewife, selling a wide array of products. Most of us have heard the pop songs as well; men with sonorous voices singing songs of sophomoric love, or women with schoolgirl voices singing of “being a fool”. The fetishization of the docile All-American, smiley housewife was at its pinnacle, and the Second World War provided the perfect excuse for capitalism. Capitalism was to become the American way, and consumers were patriots who actively fought the looming threat of communism.

Lynch was born in a small town in Montana, but his father’s job required him to move around the country, often settling in small towns. American suburbia was the poster boy for the American dream; safe streets, white picket fences, disposable income, impeccable gardens and beautiful rosy-cheeked families who spent their free time being consumers.

Now let’s fast forward a few decades. It’s 1986 and we’ve just bought tickets for Blue Velvet. Bobby Vinton’s “Blue Velvet” plays as we watch a seemingly disconnected collage of imagery: We see a clear blue sky. We see a white picket fence ornate with red roses. We see the local firefighter and his dalmatian ride through the lane, waving to the camera with a Cheshire Cat grin. A housewife watches a murder mystery on the television as her husband mysteriously falls to his death while watering his plants in the garden. Bobby Vinton’s voice fades out so we can hear the sound of insects swarming in the soil. Later, a man walking through the grass finds a dismembered ear being devoured by ants. Lynch gives new meaning to the word “eerie” (pun intended!) and brings the unsettling truth of American suburbia to the fore. The discomfort of the pain and suffering underneath that omnipresent smile that has erased the working class from pop ephemera.

Now let’s fast forward to 1989 and start listening to Floating Into the Night. The words are rather simple: trials and tribulations of young love in the style of fifties lounge singers. However, there’s one minor tweak that makes a world of difference: the recurrent mention of “night” and “darkness”, words eerily absent from songs of this ilk. It would be a stretch to pseudo-philosophize and immediately make connections that may or may not have been intended, but for me, this is where the album begins to make a statement.

It’s the Eighties. Our post-war kids have grown up. They have children of their own. It’s their prom night. They dance in circles under the disco ball as Julee Cruise sings “floating into the night” from start to finish. They float in the “night” ironically absent in the tapestry of the American “Dream”. They now dance in the viscosity of the night, the advent of their “Dream” to come.

It’s no coincidence that this album was deemed one of the pioneers of “dreampop”. The soothing wall of sound, with its synthetic, oohs and aahs, helps set a romantic tone for a slow dance, a looming kiss, intermittently interrupted by subtle hints that this is not the All-American prom night they’ve been promised throughout childhood.

The third Track “I Remember” starts slow and soothing, with a soft saxophone solo in the middle.

I remember your smile

And the way you sent it to me

So many times through different air

It lives inside my heart

And suddenly, discordant bells chime, taking us out of that comfort with unexpected words and disharmonious melody

Is it a dream?

You and me

It can’t be real

“Rocking Back Into My Heart” has a strange few lines that can be easily missed. The chorus repeats a few times:

I want you

Rockin’ back inside my heart

But before the second verse we hear:

Shadow in my house

The man, he has brown eyes

She’ll never go to Hollywood

Love moves me

I’ve ruminated upon the implications of this album for years; perhaps overthinking, overanalyzing. As a millennial, my second-hand nostalgia for the Eighties drew me towards Julee Cruise. I often listen to this album while walking through dark winter-stricken trails thinking of a passage from Emmanuel Levinas’ “Existence And Existents”:

“When the forms of things are dissolved in the night, darkness of the night, which is neither an object nor the quality of an object, invades like a presence. In the night, where we are riven to it, we are not dealing with anything. But this nothing is not that of pure nothingness. There is no longer this or that; there is not “something.” But this universal absence is in its turn presence, an absolutely unavoidable presence.”

“Night” is the ultimate unavoidable presence, of fears, of the omitted truths, of the forgotten, of the eluded fundaments of the human condition. And here, in this album, with a few soft chords, we slowly float away into its viscous night…

“That’s it! I can see her! She’s walking towards the camera!

She’s getting closer…

Now she’s starting to leave…

Fall back.

Keep falling.

Keep falling.

Keep falling.

Just go back into the woods…”

Contributors

Khashayar Mohammadi is an Iranian-born writer/toque-enthusiast based in Toronto. He is currently working as an editor for the independent publishing company Inspiritus press.

Cat Finnie is a freelance illustrator based in London, UK. She likes to create digital illustrations that have a surreal edge.

March 26, 2018

-

Guest Album Review – “Blade Runner Soundtrack” by Vangelis

This guest review was originally part of a music blog project I created called Under The Deer. Since that site won’t be around forever, I’m archiving these wonderful reviews and their accompanying illustrations here. Writer and illustrator listed at end of the review.

There is one album I’ve listened to more times than any other, and I discovered it in a way that is likely opposite from most listeners. As a child, my mother owned the soundtrack of a commercially unsuccessful science fiction movie that had come out before I was born. I would put it in an old, portable CD player and try to imagine what the movie looked like.

It began with an ominous, ethereal note and then, there was a voice.

“Enhance thirty-four to forty-six.”

A computer beeped, then there was a whirring noise.

“Pull back. Wait a minute. Go right. Stop. Enhance fifty-seven nineteen. Track forty-five left. Stop. Enhance fifteen to twenty-three. Give me a hard copy, right there.”

Then the music set in, with a glissando of what sounded like a space harpsichord and a fat, synthesized sense of mystery. It would be years until I would see Harrison Ford speak these words, or understand their significance in relation to the film’s narrative. Yet I wore that disc out, playing it over and over again. To this day, every time I watch Blade Runner, those familiar notes give me chills. Director Ridley Scott, who chose Vangelis to compose the score after hearing his Academy Award-winning work in Chariots of Fire, said, “Fundamentally, in a sentence, I’ll say [Vangelis] was the soul of the movie.”

Though Blade Runner is an 80s film, the music sounds timeless to me. I think of Amazon’s Electric Dreams, based, like Blade Runner, on the sci-fi fiction of Philip K. Dick. The episodes lack the acerbic darkness of Black Mirror, possibly because instead of being set in a bleak future the people of 2018 can imagine, they’re set in the future the people of the mid-century imagined. Blade Runner and its score feels the same way to me: someone else’s dystopian future, both beautiful and haunting.

The Blade Runner soundtrack was not released until a dozen years after the movie, in 1994. There had been bootleg versions, but this official release was the one I had. It wasn’t in chronological order. Some of the songs from the film were missing, and some tracks not featured in the film were included. “Rachael’s Song,” my favorite piece and one commonly associated with Blade Runner, was never used in the film. Here, Mary Hopkin’s melismatic vocals convey a range of emotion as they swirl over lush synth. As a kid, I would imagine a siren on a gray and rocky islet, beckoning to a passing ship. “Memories of Green” was warmer, its tinkling piano seeming to convey something fragile and important, though the futuristic whirring and beeping, combined with the title, indicated that whatever it was had long disappeared.

Mid-album, there was a song that felt older, as though it was meant to be played on a tinny radio or a parlor Victrola. “One More Kiss, Dear,” it was called, and I soon learned all the words. Scott had initially imagined The Ink Spots’ “If I Didn’t Care” (1939) for the film, yet Vangelis was able to offer an original that sounded as though it were written 40 years earlier. Peter Skellern provided the lyrics, and, interestingly enough, would later form a group called Oasis with Mary Hopkin. Not that Oasis.

“End Titles” is perhaps the only track that felt like the 80s to me, with its insistent synth bass line, made more fervent by bombastic timpani. The final track, “Tears in Rain,” was so majestically sorrowful—a simple and slow melody fading, like Roy Beatty, into obscurity.

Some of the songs were, dare I say, better without the film. The noir “Love Theme,” featuring a bawdy saxophone solo by Dick Morrissey, could be construed as romantic on its own. At the very least, it was one of the only tracks I listened to that didn’t conjure a sense of vast isolation. Yet in the film itself, Deckard aggressively coerces Rachael into a physical relationship; the scene was better in my head.

I know now that Vangelis’ score and the film are both iconic, important pieces in their respective worlds. I know that falling in love with this album was a portent for my teenage music tastes; specifically, the brooding computer music of Nine Inch Nails and Trent Reznor’s associated contemporaries. (Who am I kidding? I listen to Pretty Hate Machine and The Downward Spiral just as much as an adult.)

Yet as a kid, with no guiding narrative but the pulp album cover, these songs were an endless trove of imagination and wonder. Mostly wordless, void of lyrics save “One More Kiss, Dear” and the snippets of dialogue, I was free to build my own cinematic stories—even if I was just sitting in a rocking chair in a Midwestern home. I live in Los Angeles now, Blade Runner’s setting, little more than a year away from its starting date of November 2019. It doesn’t look anything like Blade Runner out here, but on those rare rainy days, I still put on this album and pretend.**Technically, I put on the 2002 Esper Edition, because we might not be anywhere near having hover cars in 2018, but we can stream it on YouTube.

Contributors

Juliet Bennett Rylah is a Los Angeles-based freelance writer with bylines including LA Weekly, Atlas Obscura, Nerdist, LAist, Time Out LA, and Thrillist. She’s a Halloween and cat enthusiast who loves a good monster-of-the-week TV show.

Rebecca Hendin is a multi-award winning freelance illustrator based in London. She worked as an in-house illustrator at BuzzFeed from 2015 through 2018 and is a nationally syndicated political cartoonist in the US. Freelance clients include BBC, Amnesty International, Google, Gimlet Media, New Statesman, The Nib, Politico, Island Records, Giphy, VICE, Donmar Warehouse, and more.

February 20, 2018

-

Guest Album Review – “Pinkerton” by Weezer

This guest review was originally part of a music blog project I created called Under The Deer. Since that site won’t be around forever, I’m archiving these wonderful reviews and their accompanying illustrations here. Writer and illustrator listed at end of the review.

Forget the Weezer you know today or the Weezer we were first introduced to back with their debut self-titled LP, now The Blue Album. That’s the one that gave us seminal nerd rock classics “Buddy Holly”, “Say it Ain’t So” and “Undone–The Sweater Song”.

If you want organic, free-range Weezer, Pinkerton is where it’s at. This is not to say the band hasn’t grown or evolved since 1996 or that the post-Pinkerton albums are unworthy of attention.

Rivers Cuomo, the arguably unlikely frontman of the arguably unlikely success that is Weezer, tried to distance himself and the band from Pinkerton. The same thing that made it uncomfortable for him made it the kind of album that turns casual fans into diehards. To listen to Pinkerton is to get a pretty visceral snapshot of where his head was at at that time. After 10 tracks and a scant 35 minutes, it feels like you’ve been offered an understanding of the then man-child that was and is the driving force behind Weezer.

More than that, Pinkerton changes the way you hear and perceive the rest of Weezer’s catalogue.

The album is named after the character in Madama Butterfly, the 1904 opera with which Cuomo, Weezer’s primary creative engine, was obsessed. Pinkerton (the character) is hollow, selfish and cowardly. Pinkerton (the album) details a man’s battle with the same perceived traits.

From the themes of Madama Butterfly to the Ukiyo-e album art to references to Cio-Cio San, and laid most bare in “Across the Sea”, there’s a budding interest in all things Japanese. It kicks in at key points throughout the album. Cuomo was otaku before otaku was defined in the Western sense of the Japanese word.

Lyrically, Pinkerton is a story of getting everything you thought you wanted and realizing it’s all a bit hollow. It’s the story of a man battling with himself as he works to reach some ideal that isn’t yet clear. The album isn’t maudlin, at least not musically. Present is the driving garage rock sound, courtesy (Patrick Wilson on drums, Brian Bell on guitar and Matt Sharp on bass) that typifies much of Weezer’s catalog; complex in its simplicity and vice-versa.

“Tired of Sex” kicks things off. You can probably figure out what the subject of that little ditty is. “I’m spread so thin I don’t know who I am.” Cuomo spoke in interviews about the less than glamorous realities of the glamorous rock star life. All throughout the album you hear and feel how it left him yearning for real connection. You can almost feel the furtive and ultimately unfulfilling interactions that give rise to the opening track.

“Getchoo” is the biggest hint of what future albums are going to sound like. That would be a more impressive statement if it were predictive instead of retrospective. It’s the story of someone who’s gotten used to getting what he wants but who then discovers that the tables can still be turned. From the bridge: “I can’t believe what you’ve done to me. What I did to them, you’ve done to me”

“No Other One” evokes feelings of a dysfunctional relationship as viewed through the eyes of someone with little relationship experience. The “One” in question doesn’t sound like a great partner in crime; more like the kind of person you get involved with and then stick around because fear and inertia take hold. Maybe her album would paint him in a similar light.

“Why Bother?” Part of me wishes that this (just like the rest of the tracks) didn’t bring something great to the table to make the album what it is. Then I’d be able to just say something pithy like “fair question” and move on. This is a song about not wanting to get out of your comfort zone. Of seeing something you think you really want but that you’ll never have if you can’t get over the fear of trying. I totally can’t relate.

“Across the Sea” is a song written in response to a Japanese fan letter. It starts off sweetly with a simple piano and (correct me if I’m wrong) shinobue flute. Then comes the heavy distortion over simple progressions that have always typified the band. If indeed Pinkerton offers a snapshot of where Rivers Cuomo’s head was at, “Across the Sea” demonstrates that it was a pretty confusing place at that time. The longest track on the album, it almost feels like two two-minute songs with a common thread.

“The Good Life” hits reset and says “alright, enough moping around. Let’s get back out there for some of that partying and empty sex we lamented as being ultimately unfulfilling.” It suggests maybe we’re changing gears. Maybe the back half of the album will be a little more carefree.

Not so much. Even in this song about pulling the leather rockstar pants out of storage (speaking figuratively, though if anyone could make that a good song, I’d put my money on this band) and going out to party bears the same longing and confusion as in all the other songs up to this point.

“El Scorcho” is a bit of fun but the same longing and loathing is still an undercurrent. If memorable opening phrases on a sophomore album lead single is ever a Jeopardy category, “what is Goddamn you half Japanese girls, you do it to me every time” is definitely making the board.

It’s coming from the same dark place as the rest of the album but the guitar is driving and lines about shredding on cellos and “I’m the epitome of public enemy” make it feel like a good old-fashioned MTV single.

“Pink Triangle” is a pretty good litmus for whether you’ll like the rest of the album. It unpacks the kind of infatuation that has one person building an entire relationship in their head, unbeknownst to the subject of the fantasy. It details the kind of non-relationship where the other person serves as little more than a prop. It comes crashing down when the fantasizer learns that the subject has a boyfriend or girlfriend, is not a great human, took an instant dislike to the person fantasizing. Whatever. In this case, the carefully constructed fantasy is shattered when we learn the subject is gay. Or, distilled: “I’m dumb, she’s a lesbian.”

“Falling for You” feels like the first song that isn’t laying bare some wound or weakness. I hope the fact that I’d call it the weakest link doesn’t say more about me than it does about the track.

The wrought acoustic “Butterfly” is the perfect way to end the journey. It feels like a thinly veiled metaphor for some deep wrong inflicted on an intimate friend. Or maybe it’s just Cuomo imagining Pinkerton apologizing to Cio-Cio San, aka Madama Butterfly, for being an asshole. The person that could shed light on this subject spent a long time pointedly not talking about the album, and interviewers probably have bigger, more current questions to ask.

Speaking personally, Pinkerton was a formative album. It gave me a new appreciation for and lens through which to see the band’s debut. The Blue Album can be written off as bubblegum without a deeper listen; a few hit singles, a quirky lead-off video with cute concept. Just the latest thing the industrial part of the music industry fed to kids after grunge arguably died along with one of its key icons.

Weezer helped the listeners realize that a nerd isn’t a one-dimensional character as typified in the previous generation’s pop culture. Pinkerton hit reset on what you thought you knew about Weezer.

Ask me if I like emo and you’ll get a knee-jerk no. Call me on that by pointing out that Pinkerton was kinda emo before emo was really defined and I’ll say well played, as I look sullenly out at you from behind the protective barrier of my Manic Panic Infra Red bangs.

Contributors

Andrew Moore-Crispin describes himself as a communicator, which might come as a surprise to those closest to him. He writes about all kinds of stuff (mostly tech) for all kinds of people (mostly people that are interested in tech). Music retrospective was a new challenge and one he was happy to be afforded the opportunity to tackle.

Mariel Ashlinn Kelly is an illustrator, designer, zinester and comics artist living in Toronto, Canada. She likes striped t-shirts, hanging out with her cat, and eating marshmallows straight from the bag.

February 6, 2018

-

Guest Album Review – “Big Boy” by Charlotte Cardin

This guest review was originally part of a music blog project I created called Under The Deer. Since that site won’t be around forever, I’m archiving these wonderful reviews and their accompanying illustrations here. Writer and illustrator listed at end of the review.

The Montreal singer and multi-instrumentalist, Charlotte Cardin, is my choice for the most interesting, most promising artist to emerge from a Canadian singing competition since Hedley started ruling the airwaves and Carly Rae Jepsen—who placed third on Canadian Idol in 2007—turned into a leading 1980’s pop revivalist.

After placing fourth on the first season of La Voix—the French-Canadian version of The Voice—in 2013, Cardin took the next three years to develop a style as eclectic and personal as it is accessible to mainstream listeners. On her debut E.P., Big Boy, this means upcycling pop music’s standard verse-chorus-verse song structure into a canvas for some of her strongest traits: confessional songwriting, nuanced vocals, and minimalist instrumentals that blend elements of jazz, electro, hip-hop, and R&B into grooves that’ll bob your head until it swims.

Cardin offers six songs that explore the end of love to a systematic degree, changing relationship scenarios in every song, and inhabiting the speakers with a gonzo-level of commitment that allows all of their edges to show. She is distinctive in her enunciation for being able to find new ways to bend words in the service of mood. In this way, she’s a jazz improviser, elevating Big Boy into catharsis, making words you use on a daily basis emote as you didn’t know they could.

The eponymous opening track is sultry R&B number directed at a lover who doesn’t want to take things any further than an initial tryst. Cardin delivers it with a taunting, playful tone, poking at the beloved’s lack of resolve, but also filling it with desire that betrays feelings yet to dissipate. All this is punctuated by some cascading hi-hats that back her up by being a total tease for the hypothetical recipient. She croons,

My boy is not a man yet

But boy, do I love it when you kiss my neck.

It’s the mania at having to sit with unreciprocated desire that she pulls off so well. She sounds like she is of two minds, wanting to give all of herself to the beloved but also to simultaneously take it away. The music reflects this division, the piano work awash in heavy brooding while the drums dance around her words like a devil on the shoulder.

A split mind becomes a major theme of the album and a major source of its humanity. Cardin’s protagonists aren’t afraid to express contraction amidst the anger and paranoia of their newfound solitude. We are listening to songs about people who were adored, who became integral parts of the speakers’ lives, and whose absences could entail nothing but apocalypse. There is something crushingly relatable about finding yourself to not be enough for someone and Cardin is continually tapped into it.

This is so on the single, “Like It Doesn’t Hurt” featuring Nate Husser, an electro-tinged banger that gets at the walls we put up with people who step unceremoniously out of our lives. Cardin is steely in her portrayal of the ache for a former lover whose embrace lingers like a phantom limb. Her cognitive dissonance is mirrored nicely in the lazy, pulsating synths and the dainty drum patterns they radiate from.

I’ve been around

Your body upside down,

But I can’t touch you,

In any fucking way.

She repeats this hook as if entranced by the false promises of longevity these moments of intimacy can contain. They feel too good to consider them never happening again, as opposed to their inevitably finite natures intensifying the experiences themselves.

Cardin has chemistry with Husser, who plays the lover, and whose rhymes are tightly woven with fragility hip-hop sorely lacks. The song is a picture of the unrefined anger of holding it against someone for letting their window to love you pass on by. As such, it is a moving take on the state of feeling like an open wound.

The third track, the headbanging “Dirty Dirty”, is perhaps Cardin’s greatest performance in terms of translating the ambiguity and instability of the recently dumped. She plays someone whose lover has left her for being too young, and really sharpens her tongue to convey the cosmic irony of the world withholding someone from you for being yourself.

So I can cry for my age, my life, and my face,

And I can cry ‘cause I got so much she has not

And I will wash off all the dirty, dirty thoughts I had about you.

Her words consume the boom-bap inspired beat, piling on the outrage and existential despair over handclaps that lend an arena-rock quality to the proceedings. There is a tone of entitlement that runs through the song—in that the speaker believes she deserves the relationship—that captures a universal reaction to loss with understated grace.

“Talk Talk” is an atmospheric song about sleeping with someone in your social circle and having to deal with the rumors of everyone else finding out. Continuing the trend of production mirroring subject matter, the uncertainty of the keys and drums is matched by the speaker’s declining confidence in how she is being perceived. All three trip about, on the brink of falling apart, only to implode in a visceral finale befitting the betrayal.

Cardin gives repetition a higher-order purpose here, one that turns one of pop music’s more tedious traits into a sound literary decision; namely, mimicking the obsessive dwelling that can come from being vulnerable with another person and having it blow up in your face. She creates a palpable sense of unease by returning to the shit they talk as one might poke at a sore tooth with one’s tongue, or slow down during an accident in the other lane. There is a devastating rawness to the track that comes from her openness to being a conduit for anxiety.

The two closers round off the album with an objective change in perspective. Cardin reflects on the ephemerality of love in “Les Echardes” and on the inescapability of memory in “Faufile”. Both are tender piano ballads in which she takes her emotive powers even further—French being her mother tongue—increasing the subtleties of her voice for an enjoyably more complex listen. She positions these tracks as meditations on the previous four, surveying them from the vantage point of experience, where their failures of attraction are not the catastrophes they once seemed but byproducts of wanting to get outside of herself through the hearts of others. The closers’ restrained arrangements contrast with the first four tracks’ vibrant rhythms like maturity and the experiences it comes from.

In sum, Big Boy is a concept album about unattainable love that speaks to your guts, with a singer at the helm who is unafraid to delve into the less flattering sides of desire with deeply felt fidelity. It offers beauty made from hardship, giving the work the potential to help people feel less alone about who they’ve committed to. That makes the album good literature, living laid bare, its mechanisms brought into relief for those who need to brush up on reality while they put on headphones to take a break from it.

Contributors

Trevor Abes is a Filipino-Canadian writer whose work has appeared in Torontoist, untethered, (parenthetical), Spacing Magazine, The Rusty Toque, The Theatre Reader, Hart House Review, and The Toronto Review of Books, among others.

Candela Monde is a photographer and graphic artist from Argentina. She currently lives in the city of Berlin working on her personal project called Austro, dedicated to the creation of images.

January 23, 2018

-

Guest Album Review – “Meteora” by Linkin Park

This guest review was originally part of a music blog project I created called Under The Deer. Since that site won’t be around forever, I’m archiving these wonderful reviews and their accompanying illustrations here. Writer and illustrator listed at end of the review.

Released in 2003, Meteora was the second studio album by the California-based rock band Linkin Park. It would go on to sell over 27 million copies worldwide, become seven times platinum certified, and have one song nominated for a Grammy.

I caught on to the Linkin Park craze a few years after Meteora, but remember being hooked from the moment that I heard the single “Somewhere I Belong”. As a young teenager (I think I was about 13 or 14 at the time), the nu-metal mix of Mike Shinoda’s hip-hop flow over heavy guitar and rock ‘n roll drums interspersed with DJ Mr. Hahn’s record scratches and electronic sweeps blew my mind.

But the lyrics were what really got me. The big payoff in “Somewhere I Belong” (and the twelve words that form the basis of what the song is all about) comes at the end of the chorus, when lead singer Chester Bennington wails to the world:

I want to find something I’ve wanted all along-

Somewhere I belong.

To an angsty young teenager, this was insanely relatable stuff. As I was growing and changing, losing innocence and finding vices, I was trying to learn how I fit into the world. I was trying to find somewhere I belonged, and as I listened to the words that Chester was singing, I felt like where I belonged was right there in the reverb and resonance.

So I bought the album. The first album that I ever purchased.

At its core, Meteora is an album about being angry at people that have hurt you (starting with “Don’t Stay” and clearly evident in “Faint”), but angrier at yourself for letting it happen (“Hit the Floor”, “Easier to Run”, “Figure.09”). The culmination of these emotions is the ninth track, “Breaking the Habit”, which Mike Shinoda wrote about a close family friend and which clearly alludes to stopping a painful, angry cycle of suicide. The album comes to a glorious finale in “Numb”, which ties up the overall theme by leaving the listener with the powerful chorus:

I’ve become so numb, I can’t feel you there

Become so tired, So much more aware

By becoming this, all I want to do

Is be more like me, and be less like you

Listening to these words, and the album in general, is a much more emotional experience after Chester Bennington’s tragic 2017 suicide. Every scream, wail and desperate plea becomes so much deeper and more real—we’re not just listening to a singer play a character, we’re listening to an artist crying for help. It’s raw, it’s beautiful, and it’s the reason why Meteora was not only the first album I ever purchased, but still one of my absolute favorites.

Contributors

Nate Rice is a writer and music lover based out of North Carolina that can either be found enjoying the outdoors or typing frantically away in the corner of a local coffee shop.

Rebecca Myers has always loved anything with a good story, which has inspired her to become an illustrator.

January 19, 2018

-

Guest Album Review – “Big Time” by Tom Waits

This guest review was originally part of a music blog project I created called Under The Deer. Since that site won’t be around forever, I’m archiving these wonderful reviews and their accompanying illustrations here. Writer and illustrator listed at end of the review.

There’s a particular pool of adjectives from which any Tom Waits review is bound to draw. In it are words like boozy, gravelly, gruff, strange, and carnivalesque. There’s no avoiding them, so I might as well come out and say it: Big Time—Waits’ 1988 album of hyper-energetic, belted-out live recordings—is as boozy, gravelly, gruff, strange, and carnivalesque as they come.

Big Time was released as both an album and a film; an unusual piece of musical theatre made mostly from live concert footage. Spliced in with it are brief scenes of Waits in character as Frank O’Brien—his alter-ego from Frank’s Wild Years, the one who torched his house along with his mundane suburban life and headed off on the Hollywood Freeway to follow his dreams (“Frank’s Wild Years” was first a song, then a short-lived musical play, then an album). The closest Frank ever gets to fame, Big Time suggests, is a job selling tickets and popcorn in a movie theatre. When he dozes off, he dreams of taking the stage. Waits’ real-life performances become, mind-bendingly, a figment of his own creation’s dreams.

None of this is particularly explicit, mind you. It’s more a strange mish-mash of footage used as a vehicle for delivering an album of live recordings. What’s clear is that, with Big Time, the narrative was built to fit the songs and not the other way around.

The album itself, divorced from the visuals of the film, is therefore best listened to without any narrative in mind. That’s when it becomes what it is: an 18-track distillation of Waits’ live energy. All the shrieking and pounding and grumbling and growling; all the preaching and purring and snarling and howling; immortalized, for those of us who couldn’t be there.

Most of the songs on Big Time are live versions of songs from the albums Swordfishtrombones, Rain Dogs, and Franks Wild Years. The thing about live versions is that they’re often inferior carbon copies of their studio originals: fun to listen to, but with nothing new to add. Big Time is not like that. It gives us the same songs, but in different flavors we haven’t tasted before.

Take “Red Shoes,” for example. The original had a bass line that slinked beneath the spoken word like a smoker under a streetlamp, all dark, rain-washed noir. On Big Time it’s reinvented as a hand-clapping, shoulder-shimmying track with a middle eastern influence and a fluttering Klezmer-style clarinet.

“Rain Dogs”—Waits’ anthem to the lost, the ones who have nothing, the ones who huddle in doorways but still find ways to dance and dream—becomes more urgent, the rhythmic twanging guitars engulfed by his barked-out vocals and heated growls. The live version hurtles towards its conclusion like a chaotic gypsy folk dance, twirling faster and faster each time the theme repeats. In the film version, Waits kicks his legs like a Cossack dancer, winklepickers slapping the confetti-covered floor while a fez-wearing accordionist (Willy Schwarz) goes into overdrive behind him. The whole thing is raucous, abrasive—and strangely delightful.

“Way Down In The Hole” takes the original song to a fever pitch. Waits, in character as a hellfire preacher on a mission, condemns the devil with a fire in his guts and a voice that’s drawn from every fiber of his being. “Just see if you can come up with a figure / That matches your faith,” he urges atop an ensemble of funky bass and syncopated horns that make you want to join his imaginary congregation.

Not all the songs on Big Time get you in the hips. Others are slow and heartfelt. There’s the stripped back piano and plaintive solo horn on “Ruby’s Arms”; the croaky-voiced sadness of “Train Song”; and the close-your-eyes-and-lose-yourself melancholy of “Time.”

My favorite from the album is “Cold, Cold Ground,” a song about the simple life and a riff on the familiar theme of death as the great leveler. “The piano is firewood / Times Square is the dream,” sings Waits over a major first to minor sixth chord progression that makes the harmony particularly bittersweet. Between the studio version and the Big Time version, the Mariachi-style accordion softens and melts into something more wistful. The bellows sigh, the music sways. Like the life-to-death theme, the song’s beauty is simple and devastating.

If you’re not a Tom Waits fan, your maiden voyage into Big Time might be an experience akin to having gravel poured in your ear. Waits has a voice that takes warming to; the instrumentation is unconventional, the tracks filled with clangs and sirens and whistles and clatters. Waits also happens to revel in imperfection. Bill Schimmel, a band member with the Franks Wild Years musical stage play, once recounted how Waits would urge the musicians to make deliberate mistakes, to prevent the songs from becoming too rehearsed or polished. “He’d want tricky little train wrecks in the textures,” Schimmel said.

Like the music, and like Waits’ sandpaper voice, Big Time as an album is imperfect. It’s cut together in nonsensical ways. It’s punctured by cliches and contrivances. The music is often rough and raw. The concept lacks cohesion, the narrative created for the film is fractured and forgettable. But, weirdly, Big Time’s flaws are what makes it so magical.

Why? Because imperfection invites curiosity. Because it’s the bumps in the texture that make it interesting to touch. Because to find yourself amidst a carnival of chaos—especially one of the boozy, gravelly, gruff and strange variety—is the most fun you’ll ever have.

Contributors

Tania Braukamper is an Australian-born writer. When she’s not working you can find her playing Chopin on her second-hand piano or brawling in a boxing ring. She believes in curiosity, kindness, and music as manna for the soul.

Jake Carruthers is an illustrator and designer from Toronto, Ontario. His bold style explores surreality through a clash of dark and light subject matter. His work can be found anywhere from album covers, logos, advertising, infographics and more to the merchandise of musical acts such as Good Charlotte, August Burns Red, and Monster Truck.

January 16, 2018

-

Guest Album Review – “Take Care” by Drake

This guest review was originally part of a music blog project I created called Under The Deer. Since that site won’t be around forever, I’m archiving these wonderful reviews and their accompanying illustrations here. Writer and illustrator listed at end of the review.

In his influential 2010 book Retromania, critic Simon Reynolds argues that the easy accessibility of recent pop music has had a stifling effect on creativity. Once upon a time, record labels regularly “deleted” old LPs, and few albums were reissued after their immediate release cycle. If you didn’t buy a record when it came out, it would take you no small effort if you wanted to hear it again ten years down the line, like a connoisseur of trashy video games trucking down to a landfill in Alamogordo with a spade. This had the effect of diluting influence: if you wanted your drums to sound like Can circa Tago Mago, you couldn’t just go to any old shop to buy the LP, let alone download it, let alone sample it. More often than not, you were forced to reproduce the sound in the studio as best you could recall it—and memory itself is inexact. The sound you ended up with might bear only the faintest resemblance to what you were going for, but through that flawed reproduction process, you might have stumbled onto something new.

In Reynolds’ conception, even the best music of the 2000s is pastiche and collage. Bearded indie rockers lovingly assemble records destined to be described as “Band X meets Band Y, with a hint of Band Z” by record store sommeliers, while EDM bangers recycle old material for a hit of nostalgia (sometimes cynically). I don’t entirely disagree with Reynolds’ conclusions, but it’s worth noting that the wheel has already turned from the era he was writing about. Mash-ups, the most literal example of “retromania,” have returned to the hinterlands of YouTube, while young artists seem less inclined to talk about their tapestry of influences than their social justice bona fides. The change is generational and has less to do I think with a difference in approach as it does with attitude. Being older, and a music historian to boot, when Reynolds’ hears a sample he can’t help but recall its original context; to him, most samples are by default referential. But for many new artists (and listeners), the past is simply raw material to be reduced in the service of a new vision. Reynolds could hardly have anticipated a rapper would emerge almost in tandem with his book who would embody this omnivorous and (productively) self-absorbed new status quo.

Drake’s first LP, Thank Me Later, dropped just a few months before Retromania was published, and its follow-up Take Care probably hit stores around the same time as the paperback edition. Somewhere in that 16-month window, the Canadian rapper-singer emerged fully-formed as the franchise that would go on to launch a thousand think pieces and stack up video game-level numbers on the Billboard charts. Post-808s Kanye in both production and content, Take Care establishes the basic OVO Sound, which would become as ubiquitous as Prince’s Minneapolis Sound in the ’80s: worlds of echo, muffled percussion, minimalist synths, like rain beating against the glass walls of a Toronto condo. But it’s the title track, a slight outlier on the record, that says the most about where we’re at in music today.

Decades before “Take Care” was soundtracking many a drunken, post-club reconciliation, there was “I’ll Take Care of You,” a song written by Brook Benton and first recorded by the great Bobby “Blue” Bland in 1959. Bland’s version is a smoky, hypnotic soul blues that glides along on little more than a pattering snare and a vamping Hammond organ. It was never a huge hit for Bland (#89 on the charts), but it would become a bit of a standard over the years. Crucially to our story, gravel-voiced jazz poet Gil Scott-Heron was enough of a fan to record it for his well-received 2010 comeback record I’m New Here. Now, this is where it starts to get more complicated. Scott-Heron shared a label with the xx, an English indie band whose producer Jamie “xx” Smith was subsequently hired to remix the whole record. Now titled “I’ll Take Care of U,” Jamie xx reimagined the track as a clubby yet melancholy fusion of Balearic house, dubstep, and the xx’s introspective guitar pop. Scott-Heron’s voice is scattered all over the track through echoes and spliced samples, while an icy, reverberant guitar lick serves as the song’s most instantly recognizable motif. Only then did Drake and his personal producer Noah “40” Shebib get their hands on it, adding Rihanna and cropping the title (and making just about everyone else in the tree above a bit richer).

That makes “Take Care” a (hold your breath) hip-hop interpolation of a post-dubstep remix of a postmodern blues cover of a fifty-year-old soul song. Despite this polyglot ancestry, it doesn’t play the kind of meta games with its form that Reynolds takes issue with. It feels self-contained, using these existing elements to tell its own story. In truth, 40 doesn’t make many changes to “I’ll Take Care of U” beyond simplifying the bass and drums to create a rhythmic platform for Drake’s rhymes. The more significant changes are matters of arrangement: Jamie xx’s track is house music, while Shebib’s revisions return it to a traditional pop song structure. And it’s within those familiar environs that Drake and Rihanna take over.

It helps that the two singers have such a public history, having been on-again, off-again lovers for years. While Rihanna’s biggest hits as of 2011 (“Umbrella,” “Only Girl (in the World),” “We Found Love,” the appalling “Love the Way You Lie”) seemed to reveal little about her, Drake’s palace was built on TMI. Perhaps the genuine intimacy we sense in their voices stems from their real-life closeness; or perhaps simply knowing that they are close influences our perception of the duet. However, it gets there, “Take Care” feels like an honest conversation between real people, even though the words Rihanna sings were written fifty years before Drake’s. The track wraps so snugly around their star personas it feels like it was written for them from the ground up. Drake’s performance is among his best, imbuing some of his most universal lyrics with empathy, protectiveness, and compassion.

“Take Care” occupied a unique middle ground in 2011-12’s Top 40, between the dominant pop house formula and Adele’s piano-driven torch songs, but with each passing year that middle ground has expanded. Drake himself has taken the formula to even greater chart success with tracks like “Hold On, We’re Going Home” and “One Dance,” but he’s also been joined on the pop charts by progressively weirder Lil Wayne/Drake progeny like Future, Migos and Young Thug, and genre-melting auteur statements from established artists like Beyoncé and Solange. Take Care, the album, looks more like a milestone of 2010s rap with each passing year. On the one hand, you have hints of an era just closed, like the forgotten Just Blaze banger “Lord Knows,” which sounded like a slight throwback even at the time, and the field recording of Scrooge McDuck counting his money in the studio that closes “We’ll Be Fine.” On the other, there are invaluable snapshots of future peers (Nicki Minaj, The Weeknd) and rivals (Kendrick Lamar) just prior to their own ascensions to superstar status. It even helped popularize fun ’10s tropes, like having André 3000 materialize on a deep cut and casually drop the tightest verse on the album, or relegating the hottest single to “bonus track” status (“The Motto”).

At well over 80 minutes of night-of partying, morning-after disappointment, it’s a bit of a slog even for fans, but it seems like a whole generation of listeners has come away from Take Care feeling as though their experiences at the turn of a millennium are validated by this music. Everyone’s drunk-dialed an ex who has moved on, or wanted to. Everyone has tasted some of the good life and found it more hollow than they might have imagined. Though the album snatches samples and interpolates a bevy of sources, it’s as personal a statement as any in pop music. And because we can believe this is “the real Drake,” millions have made it the soundtrack to a vital period in their own “real lives.” More than the catchphrases and memes, that will remain Drake and his collaborators’ most lasting contribution.

Contributors

JM Francheteau is a writer based in Toronto, Canada. His writing has appeared in Arc Poetry Magazine, The Puritan, Broken Pencil, Bad Nudes and elsewhere.

Mia Batajić is a visual artist, illustrator, designer, human in progress from Belgrade, Serbia. Lover of expressive art, crooked lines and color.

January 10, 2018

-

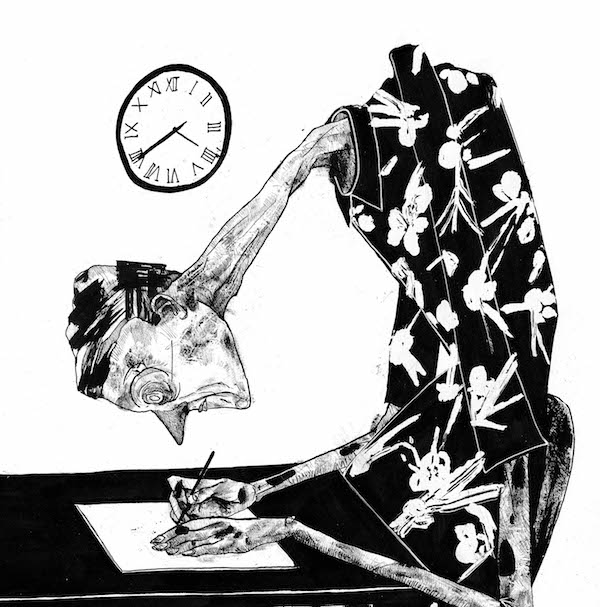

Guest Album Review – “Never For Ever” by Kate Bush

This guest review was originally part of a music blog project I created called Under The Deer. Since that site won’t be around forever, I’m archiving these wonderful reviews and their accompanying illustrations here. Writer and illustrator listed at end of the review.

When remembering the music of Kate Bush, critics usually point to 1985’s Hounds of Love, or its 1988 follow up, The Sensual World as the singer’s high points. Both are undoubtedly excellent albums, but for my money 1980’s Never For Ever is still Bush’s most compelling listen. Why? Because it represents the moment a great artist realized her full potential.

To understand the revelatory impact of Never For Ever, some context is necessary. Circa 1980, Kate Bush was a musician frustrated. She’d exploded onto the scene with her debut album, The Kick Inside in February 1978; a dramatic and bombastic blend of pop, art-rock, and prog that established the singer as a star almost overnight. That album was a labor of love, taking two years to record. But, EMI – mistakenly seeing Bush as a flash-in-the-pan phenomenon – was insistent that she bring in her second disc in a matter of months.

Coming out at the tail end of 1978, Lionheart was, by Bush’s standards, a rush job. Only three of the record’s ten tracks were newly composed for the album. The rest were leftovers from her teenage years, songs written before her debut. An uneven record, it was summarily dragged across the coals by the critics. Chris Westwood of Record Mirror was perhaps the most scathing, describing a “bland and soulless” record “which is at best moderate, lacking and often severely irritating…” Even Bush herself was openly critical of the album in interviews: “Considering how quickly we made it it’s a bloody good album, but I’m not really happy with it”.

Lionheart was a product of record label interference that undermined the reputation Bush had built for herself. Realizing that another dud could torpedo her career, the singer became the master of her own destiny on its follow-up. For the first time, she produced the record herself, affording ultimate control over the project. Peter Gabriel, whose third album Bush had appeared on, was a clear influence, both in his individualistic approach, and his choice of instrumentation. The Fairlight CMI synthesizer – a favorite tool of Gabriel’s – was utilized extensively on Never For Ever, employed to create the luscious, immersive textures that characterize the album.

When it came out in 1980, Never For Ever, was the most expansive and conceptual work that Bush had released. It is suitably Floydian in parts, unsurprising given the early mentorship that Bush received from Pink Floyd guitarist Dave Gilmour. That influence seldom dilutes the impact of Kate’s distinctive voice. This is an album where Kate Bush, as songwriter, really shines through; It often feels like an aural storybook, creating a rich tapestry of tales drawn from the annals of history, art, and popular culture. From her imagining the final years of composer Frederick Delius’ life in Delius to retelling the 1961 Brit horror film The Innocents in Infant’s Kiss, Bush’s lyrics bring a new and deeply personal perspective to old tales.

It’s an album of many strong moments. Babooshka, the record’s most well-known song, has lost none of its initial impact. Its compelling, understated, piano-driven verses contrast magnificently with the explosive, bombastic choruses, which affirm Bush’s status as one of the great voices of her generation. The Wedding List and the riotous, pseudo hard-rock of Violin are slyly witty and immaculately constructed. But it is the closing one-two punch of Army Dreamers and Breathing that is Never For Ever’s undoubted highlight. The former, a song about a mother wrestling with the guilt she feels over a soldier son’s death is sparsely arranged, with Bush’s understated vocal delivery proving particularly powerful.

Contrasting Army Dreamers’ sparsity, Breathing is a full-blown, five-minute rock opera; a tale of nuclear Armageddon uniquely told from the perspective of a fetus in utero. The song is the album’s most evocative moment, capturing the abject terror of an unborn child who, in the face of apocalyptic catastrophe can do nothing but “breathe the fall-out in. Out, in, out, in.” As the track reaches its very literal explosive crescendo (a terrifying, fictional news report announces the dropping of an atomic bomb), Bush offers her most impressive vocal moment of the record, an impassioned cry of “God give me something to breathe” that pierces over collaborator Roy Harper’s monotone and almost emotionless repetition of the phrase “what are we going to do? We are all going to die.”

The impact is lasting, resonating long after the song has finished.

37 years after its release, Never For Ever still shines as a catalytic moment for Kate Bush. It’s a fact reflected in the record’s phenomenal sales achievements; it was the first solo album by any female solo artist to enter the UK charts at number 1 and it stayed in the UK top 75 for a total of 23 weeks. But it’s not just the sales that make Never For Ever special. Powerful and compelling, displaying incredible maturity from the-then 23-year-old, it set Bush up for a string of classics – The Dreaming, Hounds of Love, The Sensual World – that are amongst the greatest albums of the 1980s. It’s because of the acclaim of those successive records that Never For Ever is often overlooked. It shouldn’t be though; it’s a forgotten classic, fully deserving of re-evaluation.

Contributors

Alec Plowman (Norwich UK) is a popular music obsessive. A journalist by day, he recently completed a Ph.D. on the history of live recordings (technically he’s a doctor of rock). When not writing about music, he plays it, fronting hard rockers Monster City.

Franco Luna is an illustrator, graphic designer and comic book enthusiast based in Mendoza, Argentina.

January 8, 2018

-

Guest Album Review – “The Bends” by Radiohead

This guest review was originally part of a music blog project I created called Under The Deer. Since that site won’t be around forever, I’m archiving these wonderful reviews and their accompanying illustrations here. Writer and illustrator listed at end of the review.

It’s hard to believe, but it’s been 20 years since Radiohead became one of the most popular rock bands in music history with their third album OK Computer. Since then, they have released another three albums that could be considered classics: Kid A, In Rainbows, and their latest release, Moon Shaped Pool. OK Computer marked the band’s progress into more experimental forms of songwriting, leading to two decades of defining trends rather than chasing them. Yet in my obsessive opinion, OK Computer isn’t Radiohead’s most important album. Their sophomore album, The Bends is.

Being Radiohead’s most traditional rock and roll release, and with Radiohead so influential on the music scene at the time, it’s an album that came to define what British rock was from 1995 to about 2006. But The Bends frequently gets lost in the mix. OK Computer and Kid A may have been game-changers in terms of what a mainstream rock band could get away with, and In Rainbows is certainly the most pleasing listen for most fans, but The Bends was a game-changer for the band, and for me.

In a way, my changing taste in music mirrored Radiohead’s change in sound. After the success of their debut album Pablo Honey, and especially their mega-single Creep, Radiohead risked painting themselves into a corner as “the British Nirvana.” While Pablo Honey isn’t a bad album – Creep, Stop Whispering, You, and Blowout remain great songs – but it sounded like a band who were battering against a sound they were never entirely comfortable with. This led to the band adopting a comparatively lighter but more intricate guitar-driven sound, coupled with Thom Yorke’s increasingly cryptic lyrics. In the same way, it was bands with a simpler rock sound, like Nirvana and, alas, Coldplay (I was young and foolish) that led me to give Radiohead a try as they promised a deeper, more rewarding listening experience. Like many, I started with OK Computer, and I still love that album to this day, but it took The Bends to show me how utterly stunning traditional rock music can be.

The opening bars of Planet Telex felt like the musical equivalent of the stargate scene in 2001: A Space Odyssey, a huge wall of sound cracked open by Phil Selway’s drums and the three-guitar attack of Jonny Greenwood, Ed O’Brien, and Thom Yorke. Like Joy Division would confirm to me later in my teens, songs with lyrics like Everything is Broken (screamed almost triumphantly) could be endlessly cathartic. It’s the band’s best opening song to date. Then the title track, which Yorke himself has said many times is just nonsense that was a lot of fun to write and play. It’s also in The Bends that Yorke first mentions a need for connection: “I want to live, breathe, I want to be a part of the human race,” a theme that would recur throughout the album.

High and Dry was the first song I heard from The Bends, and its acoustic guitar and Yorke’s cherub-like vocal made it the easiest song to connect to at first. While it was one of the singles, Yorke has stated that he hates it and that it’s the worst song about nothing he has ever written. Not to me – it still gives me chills and remains one of the band’s more popular singles to date. As does Fake Plastic Trees which is rightly regarded as one of Radiohead’s best songs. Bones left me cold for a long time, nearly a decade in fact. It took me getting a little older to understand the fear and yearning within the music. It’s one of the album’s heavier tracks, but it deals, in an almost fairy-tale fashion, with getting older. Yorke’s declaration that “I used to fly like Peter Pan” harks back to a time of childish imagination, something we all must let go of at some point.

In spite of Yorke’s more impressionistic lyrics, there are themes that recur. The aforementioned need for connection and the breakdown of relationships can be heard in (Nice Dream), The Bends, the imploding relationship in the majestic Black Star, and Street Spirit (Fade Out).

Street Spirit is an almost elusive album closer. Nothing else on the album, or indeed anywhere else in Radiohead’s discography, sounds anything like it. Yet it is intrinsic to the album beyond its status as curtain closer. If we remember Planet Telex statement that everything is broken, Street Spirit tries to move beyond that cynicism. With Yorke’s relation to death, as action and as symbol, he takes the role of himself finding power and love in life just before it ends. The last line of the album is “Immerse your soul in love,” an achingly beautiful and positive note to end an album that is often a downer. If we take The Bends as a full piece, it is a story of reconnecting with life, growing older, and embracing love, despite what its less optimistic songs might imply. I certainly didn’t see that coming on the first listen through.

As affirming as this is to me, this isn’t the only reason the album is so iconic. It has also come to define the opposite of the sophomore slump. In the mid-90s to late 00s, British bands and their progression, or lack thereof, between their debut album and their second was judged by criteria that The Bends helped create. If Oasis defined the second album being the first album but with strings, then Radiohead represented a band who made a seemingly impossible jump in quality from album number one to number two. Bands such as Coldplay, Muse, even Kasabian, and Razorlight, managed to “do a Radiohead” by releasing second albums that were vastly superior to their first. If Radiohead is now known as the band who make the trends, then The Bends was the beginning of their zeitgeist-defining status.

Contributors

A gloomy two shoes from way back, Kevin Michael Boyle will tell you that Jesus and Mary Chain are the best band to ever come out of Scotland and ignores the existence of The Proclaimers completely for obvious reasons. He has been a music critic for four years mainly due to the fact that he can barely play the triangle.

Kid Crayon is an urban contemporary painter/illustrator based in Bristol, UK. He has a love for drips and splats, with a style that is heavily influenced by hip-hop and skateboard culture.

January 5, 2018

-

Guest Album Review – “Last Date” by Eric Dolphy

This guest review was originally part of a music blog project I created called Under The Deer. Since that site won’t be around forever, I’m archiving these wonderful reviews and their accompanying illustrations here. Writer and illustrator listed at end of the review.

Out of a swell of applause emerges an acrobatic bass clarinet improvisation unlike any ever recorded. The flourish resolves into the iconic vamp of Thelonious Monk and Kenny Clarke’s jazz classic Epistrophy, launching a rendition of the tune that runs over eleven minutes. Yet it takes only those first 10 seconds to realize that you are hearing one of the preeminent reed instrument players of the 20th century.

So begins Eric Dolphy’s Last Date, an album rich with avant-garde musical invention and unrivaled virtuosity, yet shrouded in tragedy. The performance on June 2, 1964, was not Dolphy’s last concert, nor even his last to be recorded, but the title is appropriate since the album was his first recording to be released posthumously. Just twenty-seven days after this live set, the 36-year-old composer and musician died in a Berlin hospital of diabetic shock.

Dolphy’s instrumental prowess is the stuff of legend. His fluid phrasing and stunning leaps across multiple octaves on the bass clarinet, an instrument requiring massive breath support, are studied to this day by orchestral reed players at European conservatories. On flute, he could shift from the warmest, lushest classical tone to haunting, hollow, primal cries in an instant. Indeed, his dynamic feats on these two instruments make his much-admired wizardry on alto sax—the instrument for which he is best known—seem almost pedestrian.

It would be hard to imagine a better choice than Epistrophy as the album’s opener. Written in 1941, the piece was one of the first of Thelonious Monk’s many landmark compositions that propelled jazz into the modern era. Yet its driving, syncopated melodic motif perfectly embodies jazz’s street music roots. Exploiting the full range of his bass clarinet, Dolphy takes this “split personality” to the extreme. Throughout his solo, he juxtaposes relentlessly frantic, atonal phrases with tribal trills and bluesy bent notes that harken back all the way to 1920s New Orleans. Special kudos to bassist Jacques Schols for his funky, laid back, soulful solo on this track.

Although he opens and closes the piece on alto sax, Dolphy returns to bass clarinet for his solo on pianist Misha Mendelberg’s crazily named contribution to the album, Hypochristmutreefuzz. The piece is a perfect platform for Dolphy’s far-reaching melodic and harmonic experimentations.

Dolphy’s distinctive alto sound, with its blend of hints of Charlie Parker and avant-garde overtones, comes to the forefront throughout his compositions, The Madrig Speaks, The Panther Walks and Miss Ann. The first of these is an extraordinary piece of jazz writing, with a beautiful suspension of rhythm that appears cyclically throughout the piece. The main theme begins with a harmonically challenging, interval-based run landing on a dissonant trill, but the resolution of the phrase reveals Dolphy’s talent for subtle lyricism, even as he refuses to stop pushing the tension. As far as I know, no one is sure what a “madrig” is, but there are indications that the word had currency in the Black Nationalist movements of the 1960s, an intriguing possibility given both the title’s reference to a panther and the tune’s undercurrent of defiance.

In the end, it is Dolphy’s work on flute that always has been and remains my favorite element of this remarkable album. South Street Exit is an incredibly inventive take on the traditional 12-bar blues form, with a melody that beautifully embodies Dolphy’s love of unconventional arpeggios. In his solo, Dolphy alternates between aggression, introspection, and lighthearted whimsy. Arguably, however, it is Mendelberg’s bouncing, rhythmic piano solo that claims highest honors on this track. I have in fact recorded a (woefully inadequate, in my estimation) version of this piece, one of only three covers to appear among my four jazz CDs.