Month: January 2018

January 16, 2018

-

Thought

🙄

cryptocommunity

— New New York Times (@NYT_first_said) January 16, 2018

-

Thought

How do you do, fellow kids? pic.twitter.com/p5RmnpHJnm

January 15, 2018

-

Thought

I really liked the movie A Ghost Story. pic.twitter.com/NZN14pWq8a

January 14, 2018

-

Thought

I’m extremely jealous of David Letterman’s beard.

-

Thought

“Queen” (“kween”, not “keen”) is a word known by most English speakers.

“Quay” (“key”, not “kway”) is rare and most people stumble the first time they say it aloud.

One of Toronto’s tourist areas is sadistically named “Queens Quay”.

And it’s Queens not Queen’s. pic.twitter.com/Xe2727NRIC

-

Review

January 12, 2018

-

Thought

AI can probably identify your floofie friends better than you can.

https://www.blog.google/products/photos/meow-its-even-easier-find-your-furry-friends-google-photos/

January 11, 2018

-

Thought

I feel bad for Norway

-

Thought

Sometimes you’re looking forward to a productive morning and end up watching @cher and The Osmonds doing a Stevie Wonder medley.

-

Thought

I hate when that happens

Up, and very angry with my boy for lying long a bed and forgetting his lute.

— Samuel Pepys (@samuelpepys) January 11, 2018

January 10, 2018

-

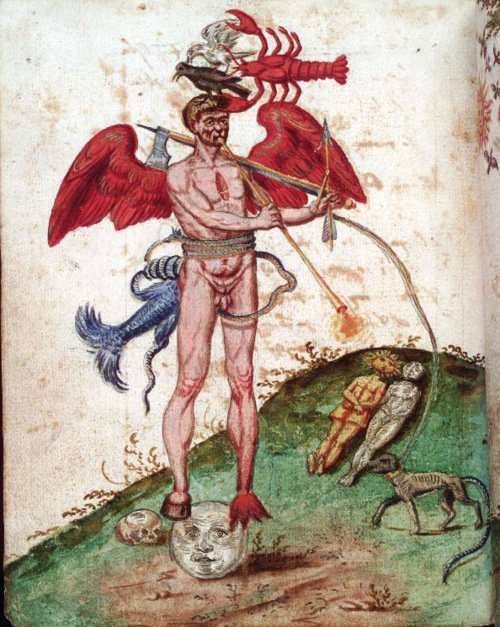

Guest Album Review – “Never For Ever” by Kate Bush

This guest review was originally part of a music blog project I created called Under The Deer. Since that site won’t be around forever, I’m archiving these wonderful reviews and their accompanying illustrations here. Writer and illustrator listed at end of the review.

When remembering the music of Kate Bush, critics usually point to 1985’s Hounds of Love, or its 1988 follow up, The Sensual World as the singer’s high points. Both are undoubtedly excellent albums, but for my money 1980’s Never For Ever is still Bush’s most compelling listen. Why? Because it represents the moment a great artist realized her full potential.

To understand the revelatory impact of Never For Ever, some context is necessary. Circa 1980, Kate Bush was a musician frustrated. She’d exploded onto the scene with her debut album, The Kick Inside in February 1978; a dramatic and bombastic blend of pop, art-rock, and prog that established the singer as a star almost overnight. That album was a labor of love, taking two years to record. But, EMI – mistakenly seeing Bush as a flash-in-the-pan phenomenon – was insistent that she bring in her second disc in a matter of months.

Coming out at the tail end of 1978, Lionheart was, by Bush’s standards, a rush job. Only three of the record’s ten tracks were newly composed for the album. The rest were leftovers from her teenage years, songs written before her debut. An uneven record, it was summarily dragged across the coals by the critics. Chris Westwood of Record Mirror was perhaps the most scathing, describing a “bland and soulless” record “which is at best moderate, lacking and often severely irritating…” Even Bush herself was openly critical of the album in interviews: “Considering how quickly we made it it’s a bloody good album, but I’m not really happy with it”.

Lionheart was a product of record label interference that undermined the reputation Bush had built for herself. Realizing that another dud could torpedo her career, the singer became the master of her own destiny on its follow-up. For the first time, she produced the record herself, affording ultimate control over the project. Peter Gabriel, whose third album Bush had appeared on, was a clear influence, both in his individualistic approach, and his choice of instrumentation. The Fairlight CMI synthesizer – a favorite tool of Gabriel’s – was utilized extensively on Never For Ever, employed to create the luscious, immersive textures that characterize the album.

When it came out in 1980, Never For Ever, was the most expansive and conceptual work that Bush had released. It is suitably Floydian in parts, unsurprising given the early mentorship that Bush received from Pink Floyd guitarist Dave Gilmour. That influence seldom dilutes the impact of Kate’s distinctive voice. This is an album where Kate Bush, as songwriter, really shines through; It often feels like an aural storybook, creating a rich tapestry of tales drawn from the annals of history, art, and popular culture. From her imagining the final years of composer Frederick Delius’ life in Delius to retelling the 1961 Brit horror film The Innocents in Infant’s Kiss, Bush’s lyrics bring a new and deeply personal perspective to old tales.

It’s an album of many strong moments. Babooshka, the record’s most well-known song, has lost none of its initial impact. Its compelling, understated, piano-driven verses contrast magnificently with the explosive, bombastic choruses, which affirm Bush’s status as one of the great voices of her generation. The Wedding List and the riotous, pseudo hard-rock of Violin are slyly witty and immaculately constructed. But it is the closing one-two punch of Army Dreamers and Breathing that is Never For Ever’s undoubted highlight. The former, a song about a mother wrestling with the guilt she feels over a soldier son’s death is sparsely arranged, with Bush’s understated vocal delivery proving particularly powerful.

Contrasting Army Dreamers’ sparsity, Breathing is a full-blown, five-minute rock opera; a tale of nuclear Armageddon uniquely told from the perspective of a fetus in utero. The song is the album’s most evocative moment, capturing the abject terror of an unborn child who, in the face of apocalyptic catastrophe can do nothing but “breathe the fall-out in. Out, in, out, in.” As the track reaches its very literal explosive crescendo (a terrifying, fictional news report announces the dropping of an atomic bomb), Bush offers her most impressive vocal moment of the record, an impassioned cry of “God give me something to breathe” that pierces over collaborator Roy Harper’s monotone and almost emotionless repetition of the phrase “what are we going to do? We are all going to die.”

The impact is lasting, resonating long after the song has finished.

37 years after its release, Never For Ever still shines as a catalytic moment for Kate Bush. It’s a fact reflected in the record’s phenomenal sales achievements; it was the first solo album by any female solo artist to enter the UK charts at number 1 and it stayed in the UK top 75 for a total of 23 weeks. But it’s not just the sales that make Never For Ever special. Powerful and compelling, displaying incredible maturity from the-then 23-year-old, it set Bush up for a string of classics – The Dreaming, Hounds of Love, The Sensual World – that are amongst the greatest albums of the 1980s. It’s because of the acclaim of those successive records that Never For Ever is often overlooked. It shouldn’t be though; it’s a forgotten classic, fully deserving of re-evaluation.

Contributors

Alec Plowman (Norwich UK) is a popular music obsessive. A journalist by day, he recently completed a Ph.D. on the history of live recordings (technically he’s a doctor of rock). When not writing about music, he plays it, fronting hard rockers Monster City.

Franco Luna is an illustrator, graphic designer and comic book enthusiast based in Mendoza, Argentina.

-

Thought

I didn’t watch the first season when it initially aired because I thought the show was about opera singers.

🤦🏻♂️

19 years. #TheSopranos pic.twitter.com/4tYloc4hb9

— HBO (@HBO) January 11, 2018

-

Thought

Sharp Dressed Men!

#archivepix pic.twitter.com/FyrAtTzDU7

— Paul Ford (@ftrain) January 10, 2018

-

Thought

💯

'Hedgehog in a Landscape' by Giovanna Garzoni (1600-1670), Italian Baroque era painter #womensart pic.twitter.com/kghMCmt9EN

— #WOMENSART (@womensart1) January 10, 2018

-

Thought

I really hope this links to a clear-eyed treatise on why they should be listening to Wolf Alice instead.

Do you love #U2 and #Oasis? You're going to want to check this out https://t.co/1m8qxThV59 pic.twitter.com/VjmAlVRZae

— blogTO (@blogTO) January 10, 2018

-

Bookmark

Phishing for Phools – Words That Matter – Medium

Illustration: Sunday Büro W e are all fools in one way or another. Fools for love, fools for vanity, fools for greed and arrogance, laziness and envy. In the fourth century AD, the Egyptian hermit Evagrius the Solitary classified human failings into eight major groups. In 590, Pope Gregory I revised…

January 8, 2018

-

Guest Album Review – “The Bends” by Radiohead

This guest review was originally part of a music blog project I created called Under The Deer. Since that site won’t be around forever, I’m archiving these wonderful reviews and their accompanying illustrations here. Writer and illustrator listed at end of the review.

It’s hard to believe, but it’s been 20 years since Radiohead became one of the most popular rock bands in music history with their third album OK Computer. Since then, they have released another three albums that could be considered classics: Kid A, In Rainbows, and their latest release, Moon Shaped Pool. OK Computer marked the band’s progress into more experimental forms of songwriting, leading to two decades of defining trends rather than chasing them. Yet in my obsessive opinion, OK Computer isn’t Radiohead’s most important album. Their sophomore album, The Bends is.

Being Radiohead’s most traditional rock and roll release, and with Radiohead so influential on the music scene at the time, it’s an album that came to define what British rock was from 1995 to about 2006. But The Bends frequently gets lost in the mix. OK Computer and Kid A may have been game-changers in terms of what a mainstream rock band could get away with, and In Rainbows is certainly the most pleasing listen for most fans, but The Bends was a game-changer for the band, and for me.

In a way, my changing taste in music mirrored Radiohead’s change in sound. After the success of their debut album Pablo Honey, and especially their mega-single Creep, Radiohead risked painting themselves into a corner as “the British Nirvana.” While Pablo Honey isn’t a bad album – Creep, Stop Whispering, You, and Blowout remain great songs – but it sounded like a band who were battering against a sound they were never entirely comfortable with. This led to the band adopting a comparatively lighter but more intricate guitar-driven sound, coupled with Thom Yorke’s increasingly cryptic lyrics. In the same way, it was bands with a simpler rock sound, like Nirvana and, alas, Coldplay (I was young and foolish) that led me to give Radiohead a try as they promised a deeper, more rewarding listening experience. Like many, I started with OK Computer, and I still love that album to this day, but it took The Bends to show me how utterly stunning traditional rock music can be.

The opening bars of Planet Telex felt like the musical equivalent of the stargate scene in 2001: A Space Odyssey, a huge wall of sound cracked open by Phil Selway’s drums and the three-guitar attack of Jonny Greenwood, Ed O’Brien, and Thom Yorke. Like Joy Division would confirm to me later in my teens, songs with lyrics like Everything is Broken (screamed almost triumphantly) could be endlessly cathartic. It’s the band’s best opening song to date. Then the title track, which Yorke himself has said many times is just nonsense that was a lot of fun to write and play. It’s also in The Bends that Yorke first mentions a need for connection: “I want to live, breathe, I want to be a part of the human race,” a theme that would recur throughout the album.

High and Dry was the first song I heard from The Bends, and its acoustic guitar and Yorke’s cherub-like vocal made it the easiest song to connect to at first. While it was one of the singles, Yorke has stated that he hates it and that it’s the worst song about nothing he has ever written. Not to me – it still gives me chills and remains one of the band’s more popular singles to date. As does Fake Plastic Trees which is rightly regarded as one of Radiohead’s best songs. Bones left me cold for a long time, nearly a decade in fact. It took me getting a little older to understand the fear and yearning within the music. It’s one of the album’s heavier tracks, but it deals, in an almost fairy-tale fashion, with getting older. Yorke’s declaration that “I used to fly like Peter Pan” harks back to a time of childish imagination, something we all must let go of at some point.

In spite of Yorke’s more impressionistic lyrics, there are themes that recur. The aforementioned need for connection and the breakdown of relationships can be heard in (Nice Dream), The Bends, the imploding relationship in the majestic Black Star, and Street Spirit (Fade Out).

Street Spirit is an almost elusive album closer. Nothing else on the album, or indeed anywhere else in Radiohead’s discography, sounds anything like it. Yet it is intrinsic to the album beyond its status as curtain closer. If we remember Planet Telex statement that everything is broken, Street Spirit tries to move beyond that cynicism. With Yorke’s relation to death, as action and as symbol, he takes the role of himself finding power and love in life just before it ends. The last line of the album is “Immerse your soul in love,” an achingly beautiful and positive note to end an album that is often a downer. If we take The Bends as a full piece, it is a story of reconnecting with life, growing older, and embracing love, despite what its less optimistic songs might imply. I certainly didn’t see that coming on the first listen through.

As affirming as this is to me, this isn’t the only reason the album is so iconic. It has also come to define the opposite of the sophomore slump. In the mid-90s to late 00s, British bands and their progression, or lack thereof, between their debut album and their second was judged by criteria that The Bends helped create. If Oasis defined the second album being the first album but with strings, then Radiohead represented a band who made a seemingly impossible jump in quality from album number one to number two. Bands such as Coldplay, Muse, even Kasabian, and Razorlight, managed to “do a Radiohead” by releasing second albums that were vastly superior to their first. If Radiohead is now known as the band who make the trends, then The Bends was the beginning of their zeitgeist-defining status.

Contributors

A gloomy two shoes from way back, Kevin Michael Boyle will tell you that Jesus and Mary Chain are the best band to ever come out of Scotland and ignores the existence of The Proclaimers completely for obvious reasons. He has been a music critic for four years mainly due to the fact that he can barely play the triangle.

Kid Crayon is an urban contemporary painter/illustrator based in Bristol, UK. He has a love for drips and splats, with a style that is heavily influenced by hip-hop and skateboard culture.

-

Thought

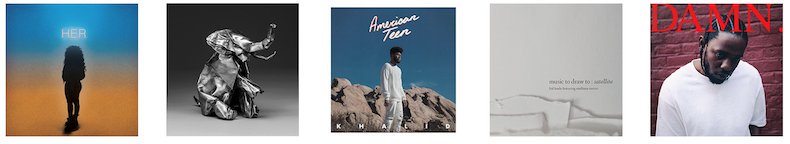

I wrote about my Top 30 Albums for the year. It was a great year for music!

https://schafer.com/top-30-albums-of-2017-f9a868898bd8

pic.twitter.com/FUdLgsjgwj

January 7, 2018

January 6, 2018

-

Top 30 Albums of 2017

A bit of background from my 2013 preamble for those new to my lists:

I do this more for me — as a way of discovering new music — than for you, but that doesn’t mean I don’t want you to get as much joy from these amazing artists as I did this year. My list-making secret is to start a “long list” of albums I like at the beginning of the year. I keep adding when something strikes my fancy and use the year-end holidays to figure out which ones really made the cut.

For those interested, my previous Top 30 Albums are still online:

- Top 30 Albums of 2010

- Top 30 Albums of 2011

- Top 30 Albums of 2012

- Top 30 Albums of 2013

- Top 30 Albums of 2014

- Top 30 Albums of 2015

- Top 30 Albums of 2016

Overall I think it was a pretty good year for music. I loved the new sounds coming out of Toronto. Drake and The Weeknd have had such an impact on the music in the city and I’d say it’s been largely positive. More of that please. And I found myself returning repeatedly to more electronic, meditative soundscapes. Not sure if it’s me or the mood of the times.

Beyond the list here, I also listed to a lot of classical — digging in to the Harmonia Mundi catalogue — and jazz — Blue Note and ECM catalogues in particular.

And now, my Top 30 Albums of 2017! Enjoy!

Note these are in alphabetical order. I could never rank these absolutely — it would change daily.

- Waiting on a Song by Dan Auerbach

- Capacity by Big Thief

- Tenderness by Blue Hawaii

- Migration by Bonobo

- Freudian by Daniel Caesar

- Theory of Colours by Dauwd

- This Old Dog by Mac Demarco

- Mirage by Flitz & Suppe

- Oczy Mlody by The Flaming Lips

- Mysterium by Hammock

- H.E.R. by H.E.R.

- Black Origami by Jlin

- American Teen by Khalid

- Music To Draw To: Satellite by Kid Koala

- Damn by Kendrick Lamar

- A Pink Sunset For No One by Noveller

- Kelly Lee Owens by Kelly Lee Owens

- The Space Between by Majid Jordan

- No Shape by Perfume Genius

- Love Songs: Part Two by Romare

- Half-Light by Rostam

- Masseduction by St Vincent

- Big Fish Theory by Vince Staples

- Fin by Syd

- Ctrl by SZA

- Lonely Planet by Tornado Wallace

- Ladilikan by Trio Da Kali & Kronos Quartet

- Scum Fuck Flower Boy by Tyler, The Creator

- Colter Wall by Colter Wall

- A Piece of the Geto by ZGTO

I’d love to know what albums we have in common and which ones you think should have made my list but didn’t. Use the comments people, don’t be shy!

-

Thought

Every year (well since 2010) I’ve published my Top 30 Albums of the year.

Here’s 2017’s list. If you think I missed anything or disagree with me, well, fight me!https://schafer.com/top-30-albums-of-2017-f9a868898bd8

-

Thought

All the smart people are saying “smart people don’t have to say they’re smart” AND, “oh btw, I’m not smart”

-

Thought

The most new wave of Saturday morning puppet show intros has to be Snelgrove Snail.

January 5, 2018

-

Guest Album Review – “Last Date” by Eric Dolphy

This guest review was originally part of a music blog project I created called Under The Deer. Since that site won’t be around forever, I’m archiving these wonderful reviews and their accompanying illustrations here. Writer and illustrator listed at end of the review.

Out of a swell of applause emerges an acrobatic bass clarinet improvisation unlike any ever recorded. The flourish resolves into the iconic vamp of Thelonious Monk and Kenny Clarke’s jazz classic Epistrophy, launching a rendition of the tune that runs over eleven minutes. Yet it takes only those first 10 seconds to realize that you are hearing one of the preeminent reed instrument players of the 20th century.

So begins Eric Dolphy’s Last Date, an album rich with avant-garde musical invention and unrivaled virtuosity, yet shrouded in tragedy. The performance on June 2, 1964, was not Dolphy’s last concert, nor even his last to be recorded, but the title is appropriate since the album was his first recording to be released posthumously. Just twenty-seven days after this live set, the 36-year-old composer and musician died in a Berlin hospital of diabetic shock.

Dolphy’s instrumental prowess is the stuff of legend. His fluid phrasing and stunning leaps across multiple octaves on the bass clarinet, an instrument requiring massive breath support, are studied to this day by orchestral reed players at European conservatories. On flute, he could shift from the warmest, lushest classical tone to haunting, hollow, primal cries in an instant. Indeed, his dynamic feats on these two instruments make his much-admired wizardry on alto sax—the instrument for which he is best known—seem almost pedestrian.

It would be hard to imagine a better choice than Epistrophy as the album’s opener. Written in 1941, the piece was one of the first of Thelonious Monk’s many landmark compositions that propelled jazz into the modern era. Yet its driving, syncopated melodic motif perfectly embodies jazz’s street music roots. Exploiting the full range of his bass clarinet, Dolphy takes this “split personality” to the extreme. Throughout his solo, he juxtaposes relentlessly frantic, atonal phrases with tribal trills and bluesy bent notes that harken back all the way to 1920s New Orleans. Special kudos to bassist Jacques Schols for his funky, laid back, soulful solo on this track.

Although he opens and closes the piece on alto sax, Dolphy returns to bass clarinet for his solo on pianist Misha Mendelberg’s crazily named contribution to the album, Hypochristmutreefuzz. The piece is a perfect platform for Dolphy’s far-reaching melodic and harmonic experimentations.

Dolphy’s distinctive alto sound, with its blend of hints of Charlie Parker and avant-garde overtones, comes to the forefront throughout his compositions, The Madrig Speaks, The Panther Walks and Miss Ann. The first of these is an extraordinary piece of jazz writing, with a beautiful suspension of rhythm that appears cyclically throughout the piece. The main theme begins with a harmonically challenging, interval-based run landing on a dissonant trill, but the resolution of the phrase reveals Dolphy’s talent for subtle lyricism, even as he refuses to stop pushing the tension. As far as I know, no one is sure what a “madrig” is, but there are indications that the word had currency in the Black Nationalist movements of the 1960s, an intriguing possibility given both the title’s reference to a panther and the tune’s undercurrent of defiance.

In the end, it is Dolphy’s work on flute that always has been and remains my favorite element of this remarkable album. South Street Exit is an incredibly inventive take on the traditional 12-bar blues form, with a melody that beautifully embodies Dolphy’s love of unconventional arpeggios. In his solo, Dolphy alternates between aggression, introspection, and lighthearted whimsy. Arguably, however, it is Mendelberg’s bouncing, rhythmic piano solo that claims highest honors on this track. I have in fact recorded a (woefully inadequate, in my estimation) version of this piece, one of only three covers to appear among my four jazz CDs.

Even if you have never made peace with the dissonances and rhythmic irregularities of modern music, you owe it to yourself to at least listen to the first two and a half minutes of the fifth track on Last Date, Dolphy’s astonishing flute rendition of the beloved standard, You Don’t Know What Love Is. His 23-second, classically constructed solo introduction is a musical flying carpet ride to another plane of existence. Building on that classically ethereal foundation, he performs his ornate but tasteful rendering of the melody accompanied only by bowed bass drones. Yet amidst all the formality and grace, Dolphy sprinkles in some of the most chillingly perfect, blues-infused pitch bends ever produced on flute.

The overall effect is at once spellbinding and heartbreaking, a powerful reminder that not one of us truly does know what love is. Yet the mystery of the search infuses every breath of a lifetime with meaning, wonder, and the most beautiful sadness.

And sadness, a vast and powerful sadness, is indeed the inevitable and appropriate emotion experienced by anyone who listens to Last Date, especially if they also watch the companion video documentary of the same title. On June 28, 1964, Eric Dolphy fell into a coma during a tour stop in Berlin. Attending physicians claimed that they had performed blood tests and identified Dolphy’s (previously undiagnosed) diabetes, but that he suffered a fatal insulin reaction when they attempted to treat his condition.

Fellow musicians and many others close to Dolphy tell a very different story. They insist that hospital staff, blinded by stereotypes, assumed that the African American jazz musician was suffering from a drug overdose and errantly assigned him to the detox ward. They either failed altogether to perform the simple blood test that could have saved him or conducted it only when they realized their error, far too late.

Which story is true, or whether the truth lies somewhere in between, we cannot know. Hospitals did not keep detailed records in the 1960s. What we do know is that Eric Dolphy most certainly was not a drug addict. He lived his whole life sober and was one of the most disciplined, hardest working musicians in all of 20th-century music. Almost certainly, his death could have been prevented with prompt diagnosis and careful treatment.

The volume of groundbreaking music that Eric Dolphy produced in the four years before his untimely death is almost beyond comprehension. What he could have accomplished with another 30, 40, 50 years or more is truly beyond imagination.

In the final seconds of Last Date, we hear Dolphy’s own words from a moment when he addressed the audience. “When you hear music,” he said, “after it’s over, it’s gone—in the air. You can never capture it again.” I wholeheartedly agree that no musical moment can ever truly be reproduced, even with the best recording technology existing today or yet to come. The performance does indeed melt into the air. But I do not accept that it is gone. A wave once formed reverberates across vast times and distances, and the musical waves Eric Dolphy created over 50 years ago still set our souls vibrating today.

Contributors

Bennett (Ben) Siems is a writer, editor, guitarist, cellist and composer who lives in Minneapolis, Minnesota USA. His writings on music have been published worldwide, and his own music has been the subject of numerous feature articles on the web and in music magazines.

Ser Sinestésico

is a surreal & psychedelic Collagist born in Buenos Aires and currently based in Berlín

.

January 4, 2018

-

Thought

1940s babydoll

1960s baby

1980s babe

2000s bae

2020s b

2040s <blueish smoke puff from left tentacle>

-

Thought

Do not tell me that Twitter is not amazing

Add Lin as Admin let’s go

— Lin-Manuel Miranda (@Lin_Manuel) January 4, 2018

-

Thought

Oh hell ya this Bruno Mars single

I’m ready for a new jack swing revival. Let’s do this 2018!

January 3, 2018

-

Thought

Twitter

http://moby.to/vi7yap

-

Thought

They’re just making up new special moons every week or two now.

A rare super blue blood moon eclipse is coming to #Toronto skies https://t.co/AX7AZBZ6yx pic.twitter.com/83L7jvKZBx

— blogTO (@blogTO) January 3, 2018