Month: January 2018

January 31, 2018

-

Thought

🤔

hicksploitation

— New New York Times (@NYT_first_said) January 31, 2018

-

Bookmark

The Author of the Acacia Seeds, Ursula K. Le Guin

This story is copyright 1974 by Ursula K. Le Guin . It is transcribed from Le Guin’s collection The Compass Rose because I’d like my friends to read it ( context ). And Other Extracts from the Journal of the Association of Therolinguistics MS. Found in an Anthill The messages were found written in…

January 29, 2018

-

Thought

Peanuts is consistently the darkest thing in my timeline.

— Peanuts On This Day (@Peanuts50YrsAgo) January 29, 2018

January 28, 2018

-

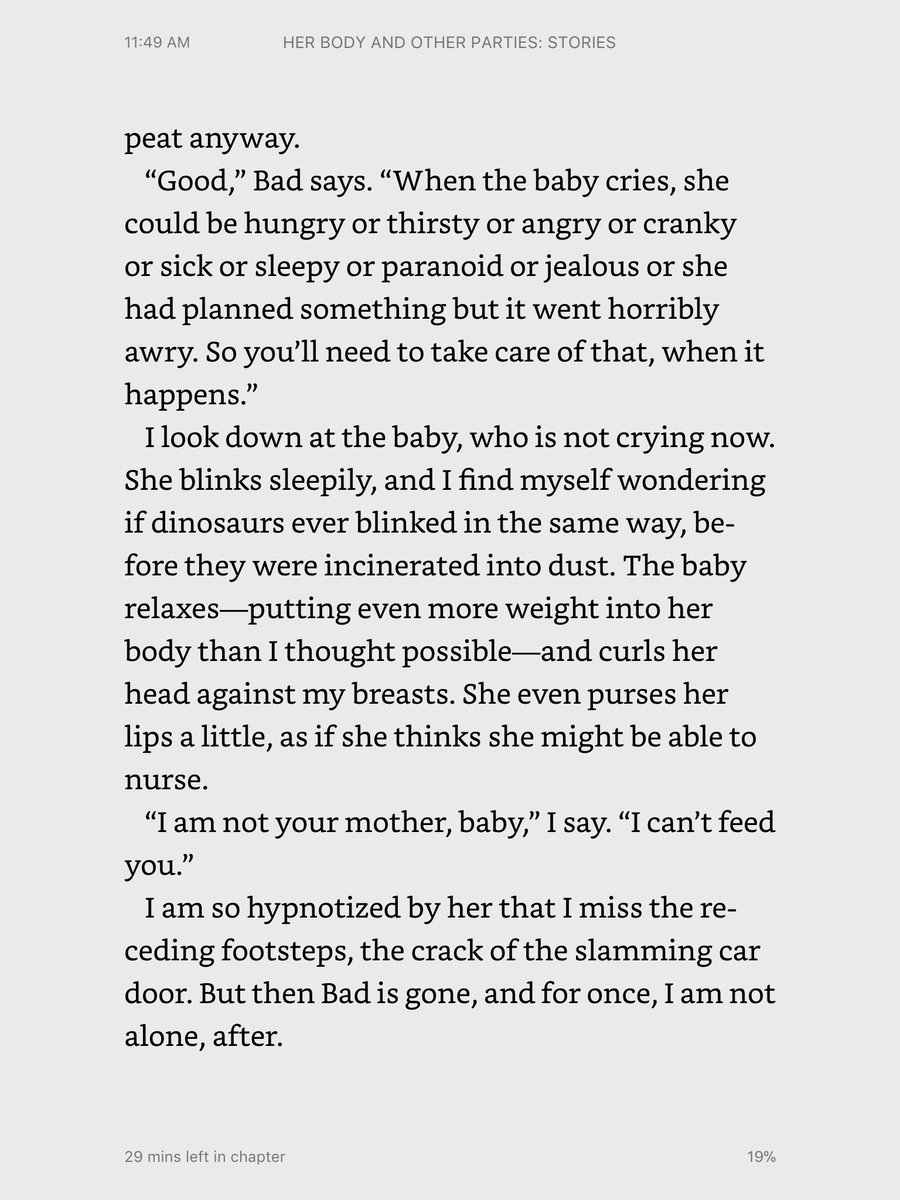

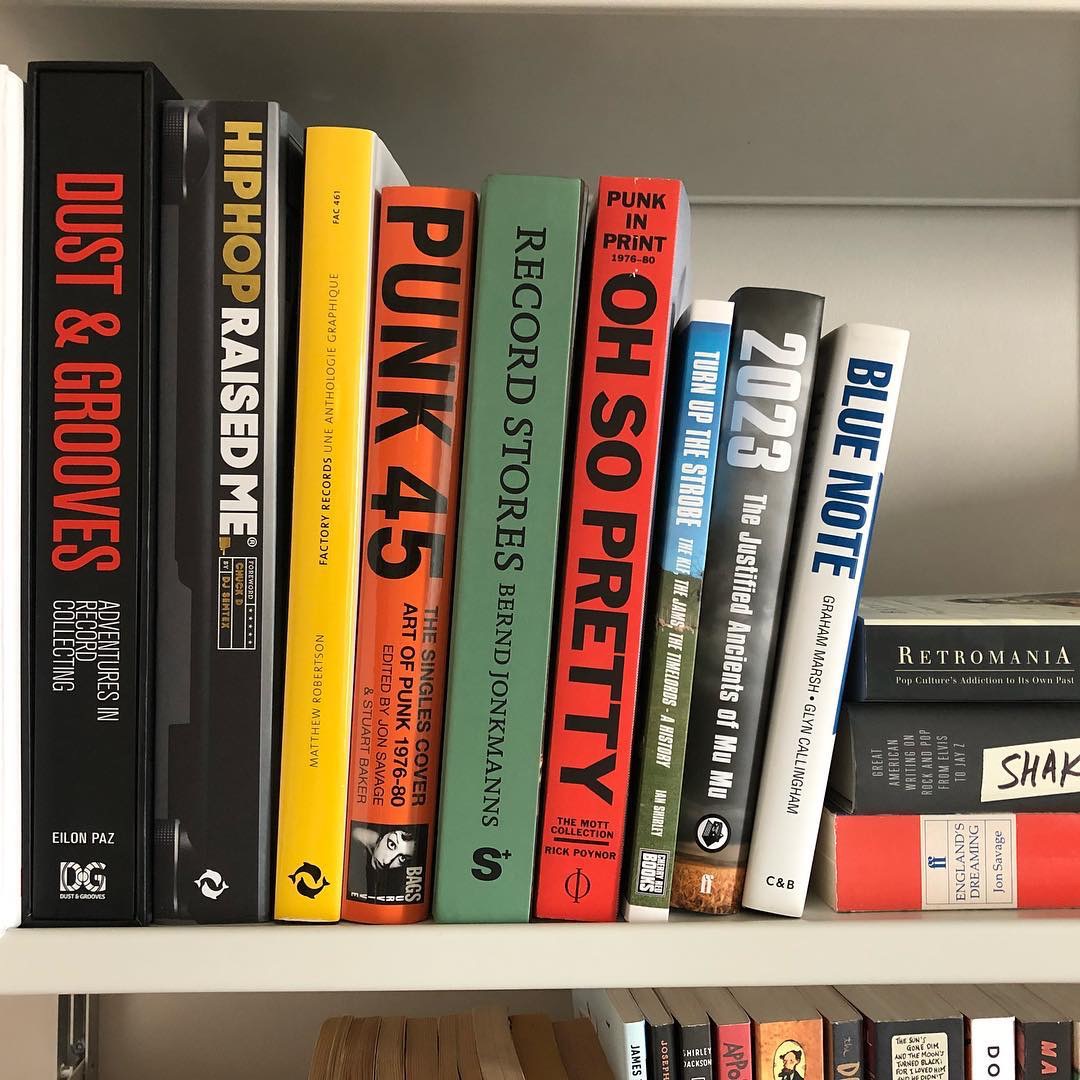

Photo

Man of words. Man of music.

-

Thought

Look at all these ghosts

(1) 1913 – Street Scenes in Stockholm, Sweden (speed corrected w/ added sound) – YouTube https://t.co/rWqUGsyKZX

— Horace Dediu (@asymco) January 28, 2018

-

Thought

January 27, 2018

January 26, 2018

January 25, 2018

-

Thought

-

Thought

My ideal writing environment would be @BearNotesApp with @grammarly inside.

Like a productivity turducken.

January 24, 2018

-

Thought

💯

She’s a very dorky girl

The kind who has a favorite Doctor

She will never let her fandom down

That’s why you read her tweetsThat girl is pretty smart now

The girl’s a super geek

The kind of girl you read about

In the the sci-fi magazines— Annalee Newitz (@Annaleen) January 25, 2018

-

Thought

I’m not happy about Big Little Lies having a second season.

-

Thought

Thank you @BurgerKing.

January 23, 2018

-

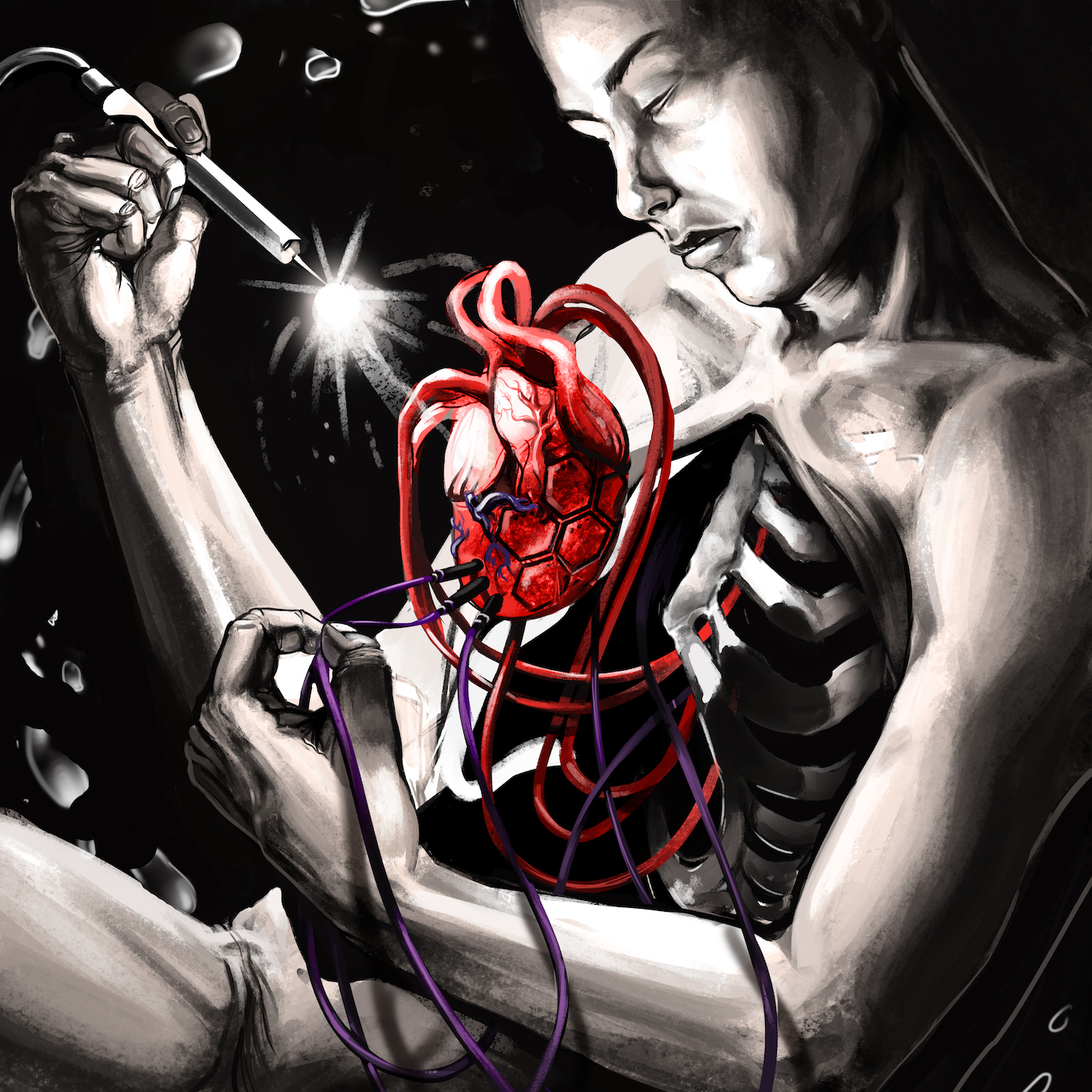

Guest Album Review – “Meteora” by Linkin Park

This guest review was originally part of a music blog project I created called Under The Deer. Since that site won’t be around forever, I’m archiving these wonderful reviews and their accompanying illustrations here. Writer and illustrator listed at end of the review.

Released in 2003, Meteora was the second studio album by the California-based rock band Linkin Park. It would go on to sell over 27 million copies worldwide, become seven times platinum certified, and have one song nominated for a Grammy.

I caught on to the Linkin Park craze a few years after Meteora, but remember being hooked from the moment that I heard the single “Somewhere I Belong”. As a young teenager (I think I was about 13 or 14 at the time), the nu-metal mix of Mike Shinoda’s hip-hop flow over heavy guitar and rock ‘n roll drums interspersed with DJ Mr. Hahn’s record scratches and electronic sweeps blew my mind.

But the lyrics were what really got me. The big payoff in “Somewhere I Belong” (and the twelve words that form the basis of what the song is all about) comes at the end of the chorus, when lead singer Chester Bennington wails to the world:

I want to find something I’ve wanted all along-

Somewhere I belong.

To an angsty young teenager, this was insanely relatable stuff. As I was growing and changing, losing innocence and finding vices, I was trying to learn how I fit into the world. I was trying to find somewhere I belonged, and as I listened to the words that Chester was singing, I felt like where I belonged was right there in the reverb and resonance.

So I bought the album. The first album that I ever purchased.

At its core, Meteora is an album about being angry at people that have hurt you (starting with “Don’t Stay” and clearly evident in “Faint”), but angrier at yourself for letting it happen (“Hit the Floor”, “Easier to Run”, “Figure.09”). The culmination of these emotions is the ninth track, “Breaking the Habit”, which Mike Shinoda wrote about a close family friend and which clearly alludes to stopping a painful, angry cycle of suicide. The album comes to a glorious finale in “Numb”, which ties up the overall theme by leaving the listener with the powerful chorus:

I’ve become so numb, I can’t feel you there

Become so tired, So much more aware

By becoming this, all I want to do

Is be more like me, and be less like you

Listening to these words, and the album in general, is a much more emotional experience after Chester Bennington’s tragic 2017 suicide. Every scream, wail and desperate plea becomes so much deeper and more real—we’re not just listening to a singer play a character, we’re listening to an artist crying for help. It’s raw, it’s beautiful, and it’s the reason why Meteora was not only the first album I ever purchased, but still one of my absolute favorites.

Contributors

Nate Rice is a writer and music lover based out of North Carolina that can either be found enjoying the outdoors or typing frantically away in the corner of a local coffee shop.

Rebecca Myers has always loved anything with a good story, which has inspired her to become an illustrator.

-

Thought

🤦🏻♂️

fitfluencers

— New New York Times (@NYT_first_said) January 23, 2018

-

Review

January 22, 2018

-

Thought

Nice

BREAKING: White House official: President Donald Trump signs bill funding government through Feb. 8, ending 69-hour shutdown.

— The Associated Press (@AP) January 23, 2018

January 20, 2018

-

Thought

I pity the incurious

-

Bookmark

The Technium: 1,000 True Fans

This is an edited, updated version of an essay I wrote in 2008 when this now popular idea was embryonic and ragged. I recently rewrote it to convey the core ideas, minus out-of-date details. This revisited essay appears in Tim Ferriss’ new book, Tools of Titans . I believe the 1,000 True Fans…

January 19, 2018

-

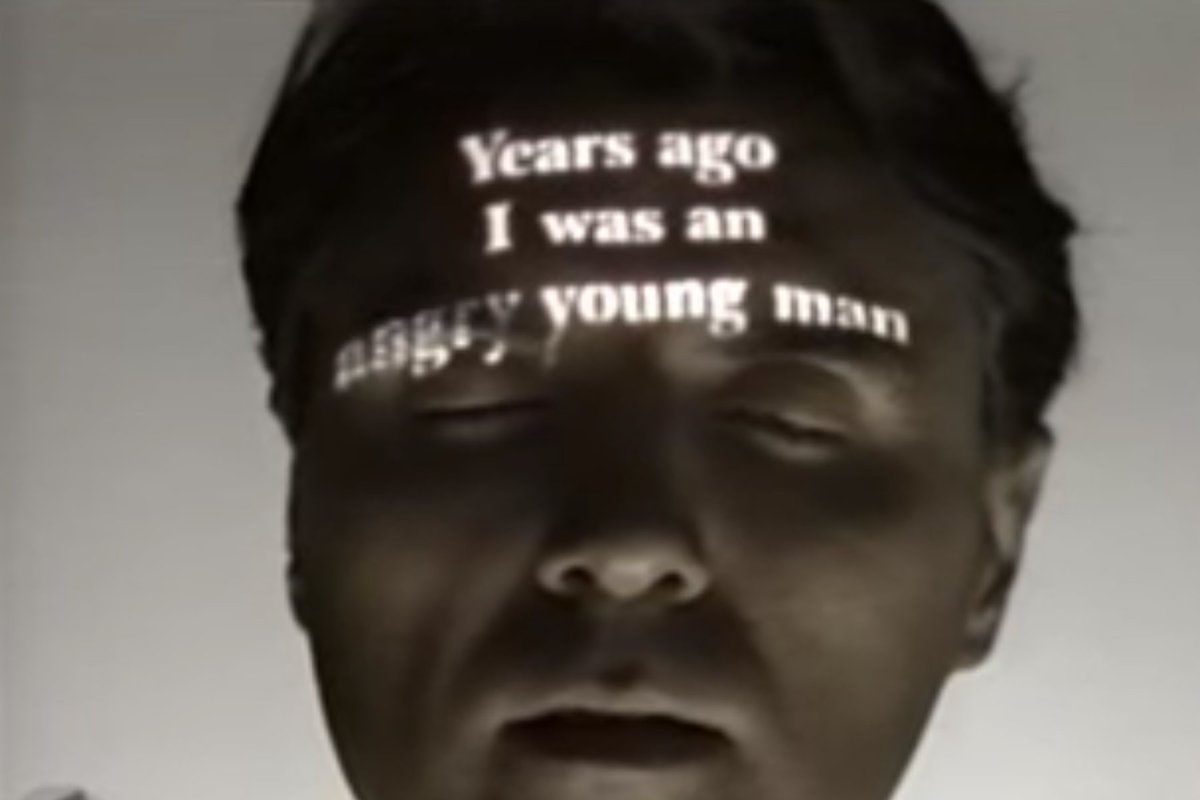

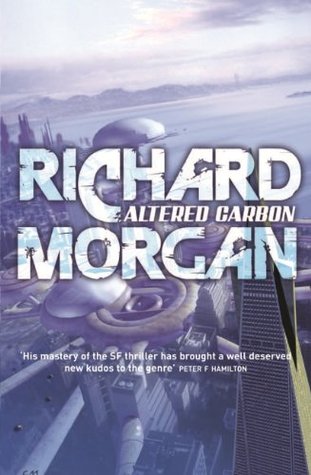

Guest Album Review – “Big Time” by Tom Waits

This guest review was originally part of a music blog project I created called Under The Deer. Since that site won’t be around forever, I’m archiving these wonderful reviews and their accompanying illustrations here. Writer and illustrator listed at end of the review.

There’s a particular pool of adjectives from which any Tom Waits review is bound to draw. In it are words like boozy, gravelly, gruff, strange, and carnivalesque. There’s no avoiding them, so I might as well come out and say it: Big Time—Waits’ 1988 album of hyper-energetic, belted-out live recordings—is as boozy, gravelly, gruff, strange, and carnivalesque as they come.

Big Time was released as both an album and a film; an unusual piece of musical theatre made mostly from live concert footage. Spliced in with it are brief scenes of Waits in character as Frank O’Brien—his alter-ego from Frank’s Wild Years, the one who torched his house along with his mundane suburban life and headed off on the Hollywood Freeway to follow his dreams (“Frank’s Wild Years” was first a song, then a short-lived musical play, then an album). The closest Frank ever gets to fame, Big Time suggests, is a job selling tickets and popcorn in a movie theatre. When he dozes off, he dreams of taking the stage. Waits’ real-life performances become, mind-bendingly, a figment of his own creation’s dreams.

None of this is particularly explicit, mind you. It’s more a strange mish-mash of footage used as a vehicle for delivering an album of live recordings. What’s clear is that, with Big Time, the narrative was built to fit the songs and not the other way around.

The album itself, divorced from the visuals of the film, is therefore best listened to without any narrative in mind. That’s when it becomes what it is: an 18-track distillation of Waits’ live energy. All the shrieking and pounding and grumbling and growling; all the preaching and purring and snarling and howling; immortalized, for those of us who couldn’t be there.

Most of the songs on Big Time are live versions of songs from the albums Swordfishtrombones, Rain Dogs, and Franks Wild Years. The thing about live versions is that they’re often inferior carbon copies of their studio originals: fun to listen to, but with nothing new to add. Big Time is not like that. It gives us the same songs, but in different flavors we haven’t tasted before.

Take “Red Shoes,” for example. The original had a bass line that slinked beneath the spoken word like a smoker under a streetlamp, all dark, rain-washed noir. On Big Time it’s reinvented as a hand-clapping, shoulder-shimmying track with a middle eastern influence and a fluttering Klezmer-style clarinet.

“Rain Dogs”—Waits’ anthem to the lost, the ones who have nothing, the ones who huddle in doorways but still find ways to dance and dream—becomes more urgent, the rhythmic twanging guitars engulfed by his barked-out vocals and heated growls. The live version hurtles towards its conclusion like a chaotic gypsy folk dance, twirling faster and faster each time the theme repeats. In the film version, Waits kicks his legs like a Cossack dancer, winklepickers slapping the confetti-covered floor while a fez-wearing accordionist (Willy Schwarz) goes into overdrive behind him. The whole thing is raucous, abrasive—and strangely delightful.

“Way Down In The Hole” takes the original song to a fever pitch. Waits, in character as a hellfire preacher on a mission, condemns the devil with a fire in his guts and a voice that’s drawn from every fiber of his being. “Just see if you can come up with a figure / That matches your faith,” he urges atop an ensemble of funky bass and syncopated horns that make you want to join his imaginary congregation.

Not all the songs on Big Time get you in the hips. Others are slow and heartfelt. There’s the stripped back piano and plaintive solo horn on “Ruby’s Arms”; the croaky-voiced sadness of “Train Song”; and the close-your-eyes-and-lose-yourself melancholy of “Time.”

My favorite from the album is “Cold, Cold Ground,” a song about the simple life and a riff on the familiar theme of death as the great leveler. “The piano is firewood / Times Square is the dream,” sings Waits over a major first to minor sixth chord progression that makes the harmony particularly bittersweet. Between the studio version and the Big Time version, the Mariachi-style accordion softens and melts into something more wistful. The bellows sigh, the music sways. Like the life-to-death theme, the song’s beauty is simple and devastating.

If you’re not a Tom Waits fan, your maiden voyage into Big Time might be an experience akin to having gravel poured in your ear. Waits has a voice that takes warming to; the instrumentation is unconventional, the tracks filled with clangs and sirens and whistles and clatters. Waits also happens to revel in imperfection. Bill Schimmel, a band member with the Franks Wild Years musical stage play, once recounted how Waits would urge the musicians to make deliberate mistakes, to prevent the songs from becoming too rehearsed or polished. “He’d want tricky little train wrecks in the textures,” Schimmel said.

Like the music, and like Waits’ sandpaper voice, Big Time as an album is imperfect. It’s cut together in nonsensical ways. It’s punctured by cliches and contrivances. The music is often rough and raw. The concept lacks cohesion, the narrative created for the film is fractured and forgettable. But, weirdly, Big Time’s flaws are what makes it so magical.

Why? Because imperfection invites curiosity. Because it’s the bumps in the texture that make it interesting to touch. Because to find yourself amidst a carnival of chaos—especially one of the boozy, gravelly, gruff and strange variety—is the most fun you’ll ever have.

Contributors

Tania Braukamper is an Australian-born writer. When she’s not working you can find her playing Chopin on her second-hand piano or brawling in a boxing ring. She believes in curiosity, kindness, and music as manna for the soul.

Jake Carruthers is an illustrator and designer from Toronto, Ontario. His bold style explores surreality through a clash of dark and light subject matter. His work can be found anywhere from album covers, logos, advertising, infographics and more to the merchandise of musical acts such as Good Charlotte, August Burns Red, and Monster Truck.

-

Thought

I’ve got a soft spot for goofy one-hit wonders.

January 18, 2018

-

Thought

ROYGBIV

the only game i play on my phone is the one where you arrange your apps like a psycho pic.twitter.com/x6NG7dO8yU

— Braaaaaaaaaaandoooon (@brandonhaslegs) January 18, 2018

-

Thought

Netflix’ “Godless” most be the most beautifully shot TV drama ever. In part because it’s available in 4K HDR.

January 16, 2018

-

Guest Album Review – “Take Care” by Drake

This guest review was originally part of a music blog project I created called Under The Deer. Since that site won’t be around forever, I’m archiving these wonderful reviews and their accompanying illustrations here. Writer and illustrator listed at end of the review.

In his influential 2010 book Retromania, critic Simon Reynolds argues that the easy accessibility of recent pop music has had a stifling effect on creativity. Once upon a time, record labels regularly “deleted” old LPs, and few albums were reissued after their immediate release cycle. If you didn’t buy a record when it came out, it would take you no small effort if you wanted to hear it again ten years down the line, like a connoisseur of trashy video games trucking down to a landfill in Alamogordo with a spade. This had the effect of diluting influence: if you wanted your drums to sound like Can circa Tago Mago, you couldn’t just go to any old shop to buy the LP, let alone download it, let alone sample it. More often than not, you were forced to reproduce the sound in the studio as best you could recall it—and memory itself is inexact. The sound you ended up with might bear only the faintest resemblance to what you were going for, but through that flawed reproduction process, you might have stumbled onto something new.

In Reynolds’ conception, even the best music of the 2000s is pastiche and collage. Bearded indie rockers lovingly assemble records destined to be described as “Band X meets Band Y, with a hint of Band Z” by record store sommeliers, while EDM bangers recycle old material for a hit of nostalgia (sometimes cynically). I don’t entirely disagree with Reynolds’ conclusions, but it’s worth noting that the wheel has already turned from the era he was writing about. Mash-ups, the most literal example of “retromania,” have returned to the hinterlands of YouTube, while young artists seem less inclined to talk about their tapestry of influences than their social justice bona fides. The change is generational and has less to do I think with a difference in approach as it does with attitude. Being older, and a music historian to boot, when Reynolds’ hears a sample he can’t help but recall its original context; to him, most samples are by default referential. But for many new artists (and listeners), the past is simply raw material to be reduced in the service of a new vision. Reynolds could hardly have anticipated a rapper would emerge almost in tandem with his book who would embody this omnivorous and (productively) self-absorbed new status quo.

Drake’s first LP, Thank Me Later, dropped just a few months before Retromania was published, and its follow-up Take Care probably hit stores around the same time as the paperback edition. Somewhere in that 16-month window, the Canadian rapper-singer emerged fully-formed as the franchise that would go on to launch a thousand think pieces and stack up video game-level numbers on the Billboard charts. Post-808s Kanye in both production and content, Take Care establishes the basic OVO Sound, which would become as ubiquitous as Prince’s Minneapolis Sound in the ’80s: worlds of echo, muffled percussion, minimalist synths, like rain beating against the glass walls of a Toronto condo. But it’s the title track, a slight outlier on the record, that says the most about where we’re at in music today.

Decades before “Take Care” was soundtracking many a drunken, post-club reconciliation, there was “I’ll Take Care of You,” a song written by Brook Benton and first recorded by the great Bobby “Blue” Bland in 1959. Bland’s version is a smoky, hypnotic soul blues that glides along on little more than a pattering snare and a vamping Hammond organ. It was never a huge hit for Bland (#89 on the charts), but it would become a bit of a standard over the years. Crucially to our story, gravel-voiced jazz poet Gil Scott-Heron was enough of a fan to record it for his well-received 2010 comeback record I’m New Here. Now, this is where it starts to get more complicated. Scott-Heron shared a label with the xx, an English indie band whose producer Jamie “xx” Smith was subsequently hired to remix the whole record. Now titled “I’ll Take Care of U,” Jamie xx reimagined the track as a clubby yet melancholy fusion of Balearic house, dubstep, and the xx’s introspective guitar pop. Scott-Heron’s voice is scattered all over the track through echoes and spliced samples, while an icy, reverberant guitar lick serves as the song’s most instantly recognizable motif. Only then did Drake and his personal producer Noah “40” Shebib get their hands on it, adding Rihanna and cropping the title (and making just about everyone else in the tree above a bit richer).

That makes “Take Care” a (hold your breath) hip-hop interpolation of a post-dubstep remix of a postmodern blues cover of a fifty-year-old soul song. Despite this polyglot ancestry, it doesn’t play the kind of meta games with its form that Reynolds takes issue with. It feels self-contained, using these existing elements to tell its own story. In truth, 40 doesn’t make many changes to “I’ll Take Care of U” beyond simplifying the bass and drums to create a rhythmic platform for Drake’s rhymes. The more significant changes are matters of arrangement: Jamie xx’s track is house music, while Shebib’s revisions return it to a traditional pop song structure. And it’s within those familiar environs that Drake and Rihanna take over.

It helps that the two singers have such a public history, having been on-again, off-again lovers for years. While Rihanna’s biggest hits as of 2011 (“Umbrella,” “Only Girl (in the World),” “We Found Love,” the appalling “Love the Way You Lie”) seemed to reveal little about her, Drake’s palace was built on TMI. Perhaps the genuine intimacy we sense in their voices stems from their real-life closeness; or perhaps simply knowing that they are close influences our perception of the duet. However, it gets there, “Take Care” feels like an honest conversation between real people, even though the words Rihanna sings were written fifty years before Drake’s. The track wraps so snugly around their star personas it feels like it was written for them from the ground up. Drake’s performance is among his best, imbuing some of his most universal lyrics with empathy, protectiveness, and compassion.

“Take Care” occupied a unique middle ground in 2011-12’s Top 40, between the dominant pop house formula and Adele’s piano-driven torch songs, but with each passing year that middle ground has expanded. Drake himself has taken the formula to even greater chart success with tracks like “Hold On, We’re Going Home” and “One Dance,” but he’s also been joined on the pop charts by progressively weirder Lil Wayne/Drake progeny like Future, Migos and Young Thug, and genre-melting auteur statements from established artists like Beyoncé and Solange. Take Care, the album, looks more like a milestone of 2010s rap with each passing year. On the one hand, you have hints of an era just closed, like the forgotten Just Blaze banger “Lord Knows,” which sounded like a slight throwback even at the time, and the field recording of Scrooge McDuck counting his money in the studio that closes “We’ll Be Fine.” On the other, there are invaluable snapshots of future peers (Nicki Minaj, The Weeknd) and rivals (Kendrick Lamar) just prior to their own ascensions to superstar status. It even helped popularize fun ’10s tropes, like having André 3000 materialize on a deep cut and casually drop the tightest verse on the album, or relegating the hottest single to “bonus track” status (“The Motto”).

At well over 80 minutes of night-of partying, morning-after disappointment, it’s a bit of a slog even for fans, but it seems like a whole generation of listeners has come away from Take Care feeling as though their experiences at the turn of a millennium are validated by this music. Everyone’s drunk-dialed an ex who has moved on, or wanted to. Everyone has tasted some of the good life and found it more hollow than they might have imagined. Though the album snatches samples and interpolates a bevy of sources, it’s as personal a statement as any in pop music. And because we can believe this is “the real Drake,” millions have made it the soundtrack to a vital period in their own “real lives.” More than the catchphrases and memes, that will remain Drake and his collaborators’ most lasting contribution.

Contributors

JM Francheteau is a writer based in Toronto, Canada. His writing has appeared in Arc Poetry Magazine, The Puritan, Broken Pencil, Bad Nudes and elsewhere.

Mia Batajić is a visual artist, illustrator, designer, human in progress from Belgrade, Serbia. Lover of expressive art, crooked lines and color.

-

Thought

I feel like maybe we’re getting carried away with putting feathers on dinos

A newly discovered dinosaur likely had iridescent feathers that gave it a rainbow appearance. 🌈 Caihong juji (“rainbow with the big crest” in Mandarin) was a duck-sized dino living 161 million years ago. https://t.co/Yv17q6i4wQ pic.twitter.com/g0AdU9HHoS

— Field Museum (@FieldMuseum) January 15, 2018

-

Thought

💡

“Giphy for old people”

All gifs are from Johnny Carson, Bob Newhart, Carol Burnett, Leave it to Beaver, and the Ed Sullivan show.

-

Thought

Managing calendars, contacts, and tasks are unsolved and I’m starting to think, unsolvable, problems.

-

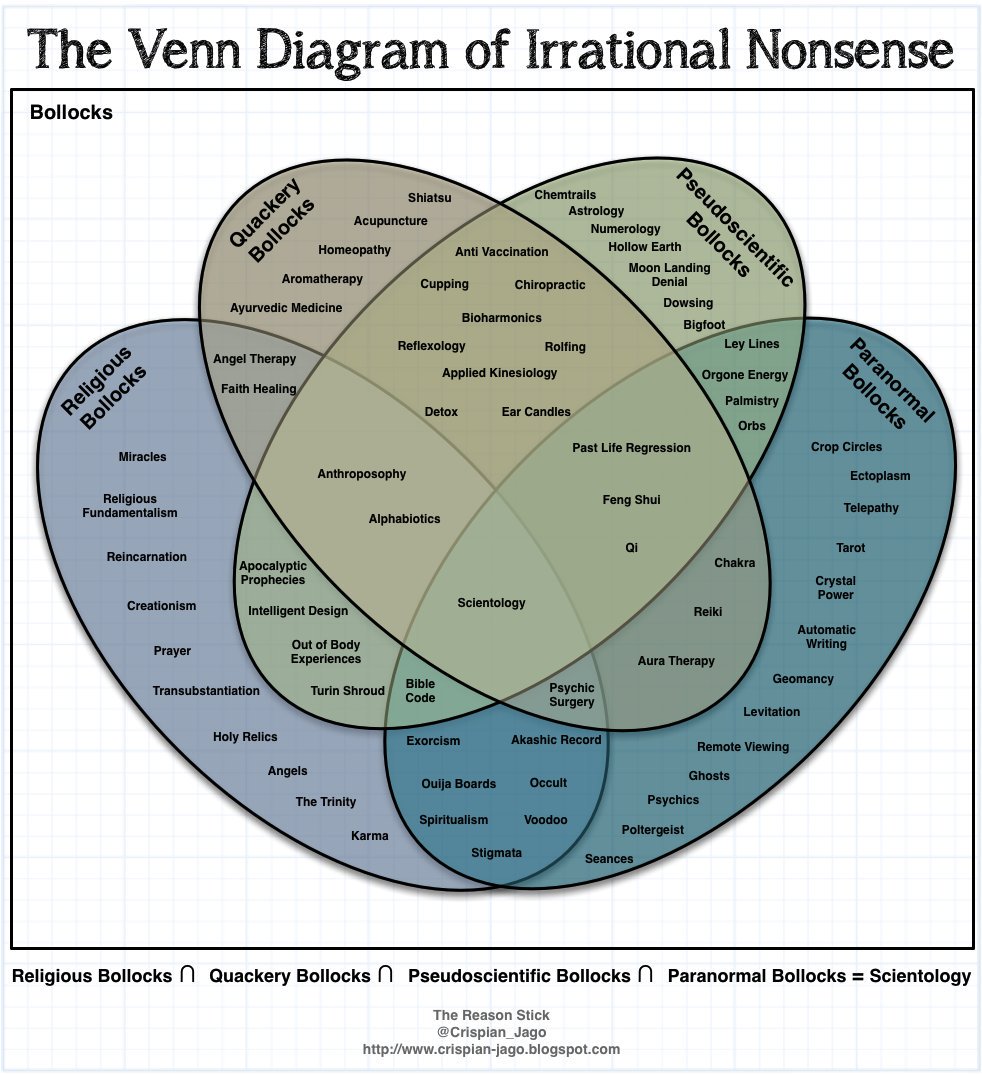

Thought

Oprah helped create our American fantasyland via decades of pseudoscience promotion:

https://slate.com/health-and-science/2018/01/oprah-winfrey-helped-create-our-irrational-pseudoscientific-american-fantasyland.html?wpsrc=sh_all_dt_tw_ru

pic.twitter.com/sqQOHLtoRu -

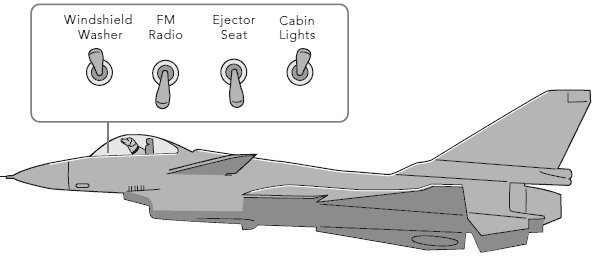

Thought

Sure the UI has some issues, but I hope we can all agree the real problem here is letting dogs be pilots. pic.twitter.com/0xYp2Wnpza

-

Thought

— Peanuts On This Day (@Peanuts50YrsAgo) January 16, 2018